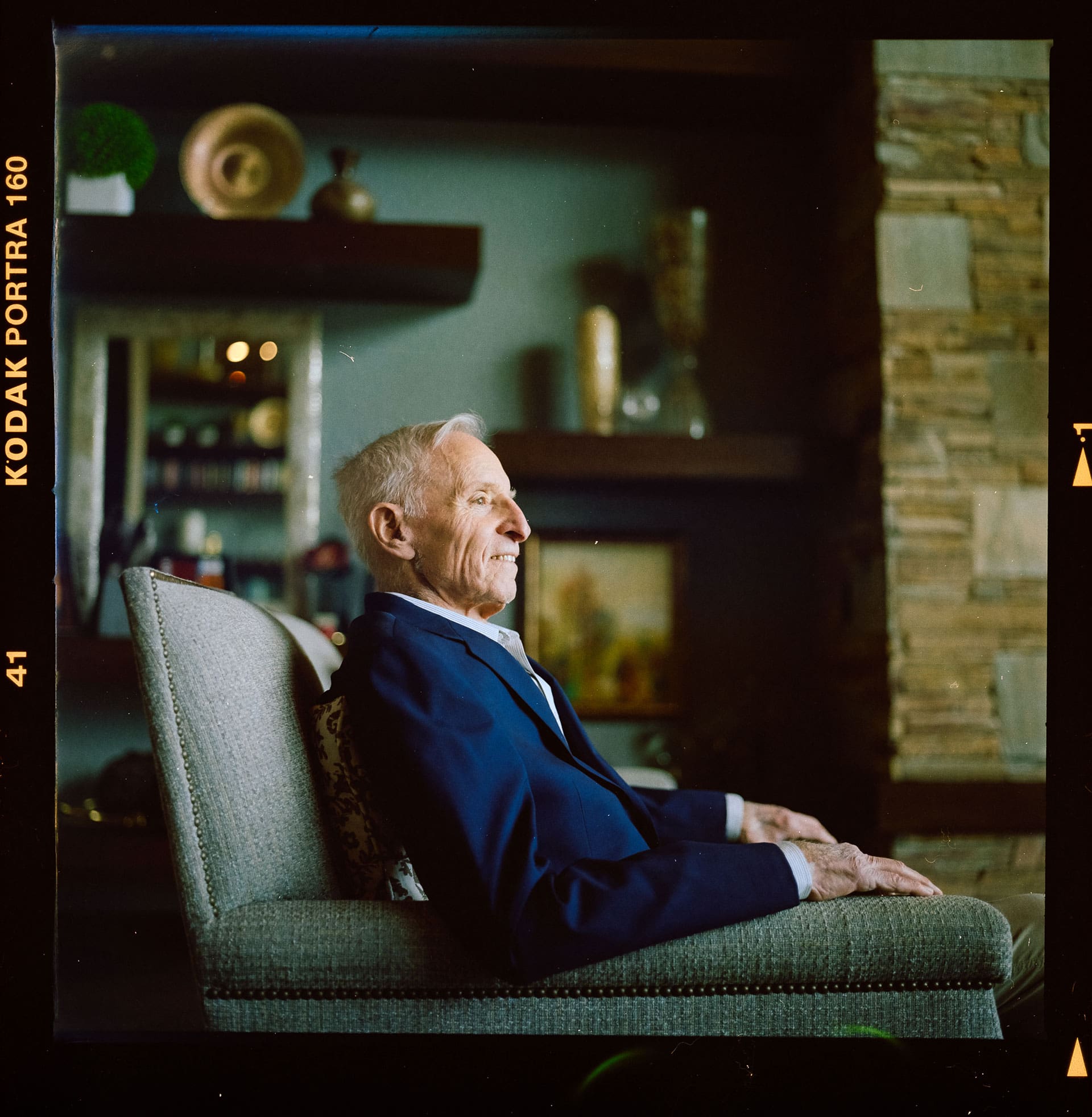

Early in Dr. Jim Krasno’s autobiographical book, I’d Rather Do an Autopsy, there’s a scene where he arrives at a prison for the first time. Jim was a pathologist for over forty years in the Bay Area. Pathology is an investigative form of medicine: You’re using the human body to unlock secrets about death and disease.

Jim’s stories about his career read like scenes from a Raymond Chandler novel: He conducted autopsies on murder victims, testified in court, and spent seven years overseeing lab work on prisoners. He also managed rental properties and developed a line of Mortuwear clothing on the side. (“Clothing designed for the morgue, now available for the street.”)

The scene in his book where he arrives at prison captures Jim’s dry sense of humor. As he waits in a long line to enter, a prison guard shouts to him, “You can’t go in dressed like that.” Jim is confused—he’s wearing normal clothes—until the guard explains, “You can’t wear anything blue. In a lockdown, we shoot at anything blue. Only the prisoners wear blue.”

It’s a moment teetering on the edge of danger, and it’s typical of Jim’s career experiences. He has worked hard at living an interesting life, preferring risky opportunities to boredom. He calls himself a medical entrepreneur.

He likely inherited the entrepreneurial spirit from his family—but they encouraged him to pursue medicine.

JIM:

I grew up in Whitefish Bay, Wisconsin. In a Jewish family in Wisconsin, you wanted your son to be a doctor.

My grandparents on both sides came over from Eastern Europe at the turn of last century. And my father’s father was in manufacturing. He started a clothing factory in Milwaukee.

My grandfather loved the idea of his grandson being a doctor.

Jim was pre-med at Yale University. Still, he wouldn’t have gone to medical school right away were it not for the Vietnam War: The threat of the draft loomed over his graduating class.

JIM:

I had a recent luncheon with 25 of my classmates, and they all said the Vietnam War changed their careers.

He attended Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, trained as a pathologist at UNC Chapel Hill and UC San Diego, then moved to San Francisco in 1973.

JIM:

When I grew up, I knew I wanted to be where more was going on. San Francisco was the place to go. It was beautiful. You could go anywhere, do anything.

He initially took a normal pathology job.

JIM:

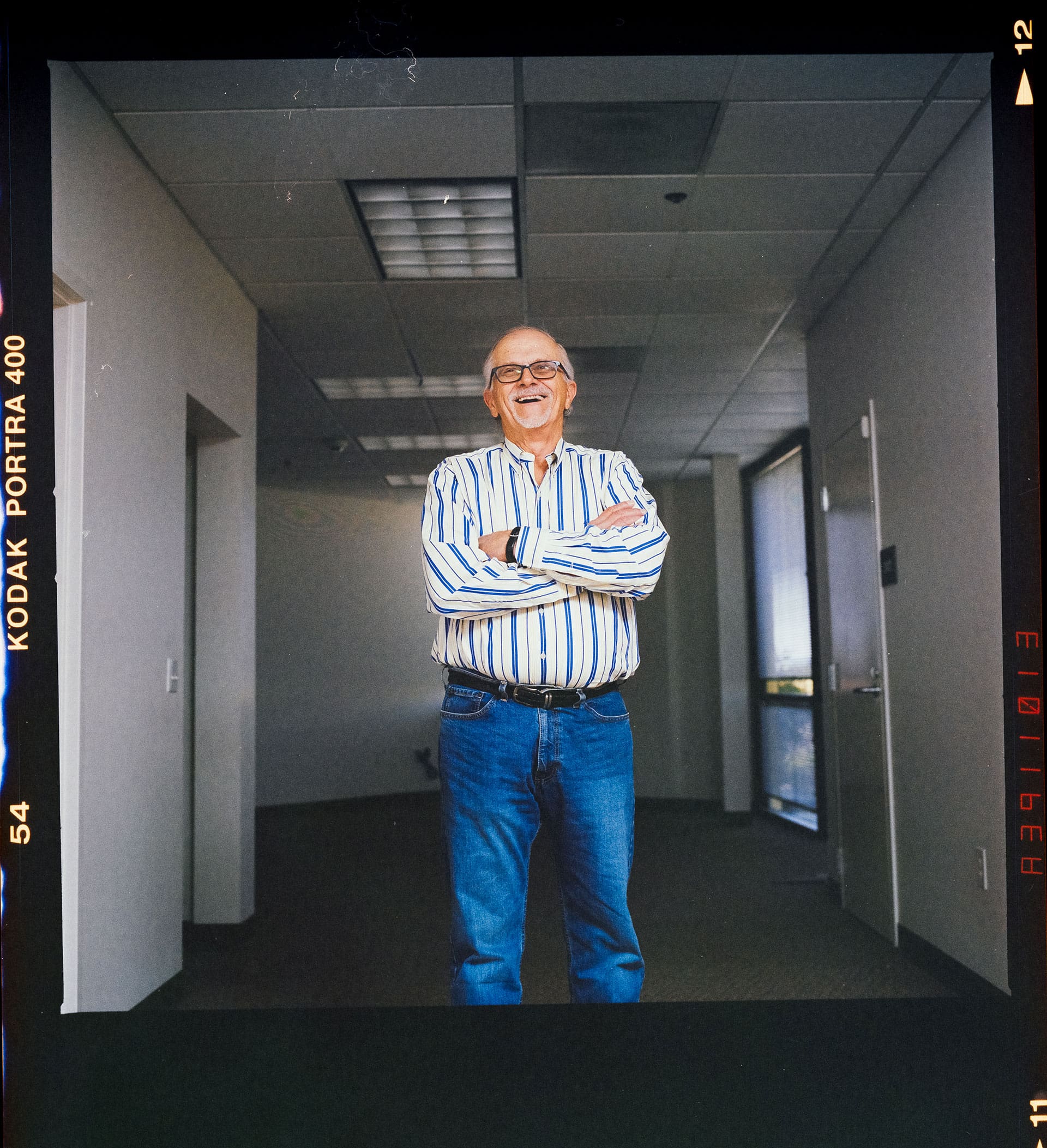

I worked for several years sitting at a microscope looking at slides in hospitals. I decided that wasn’t quite right. I wanted to go out on my own. I wanted to be independent.

He started marketing his own pathology practice. He took contracts for pathology at hospitals, coroners’ offices, and outside laboratories. He was good at his job. At one point, a big Sacramento laboratory hired Jim to take over as director of pathology—and Jim discovered the lab had a contract to provide a pathologist to the nearby prison hospital.

JIM:

As the head of pathology, I was responsible for covering the practice at the prison. None of the other pathologists would do it. They all said they’d quit if they had to go to the prison. So I did it. This was a great opportunity.

I took a lot of borderline things that paid off.

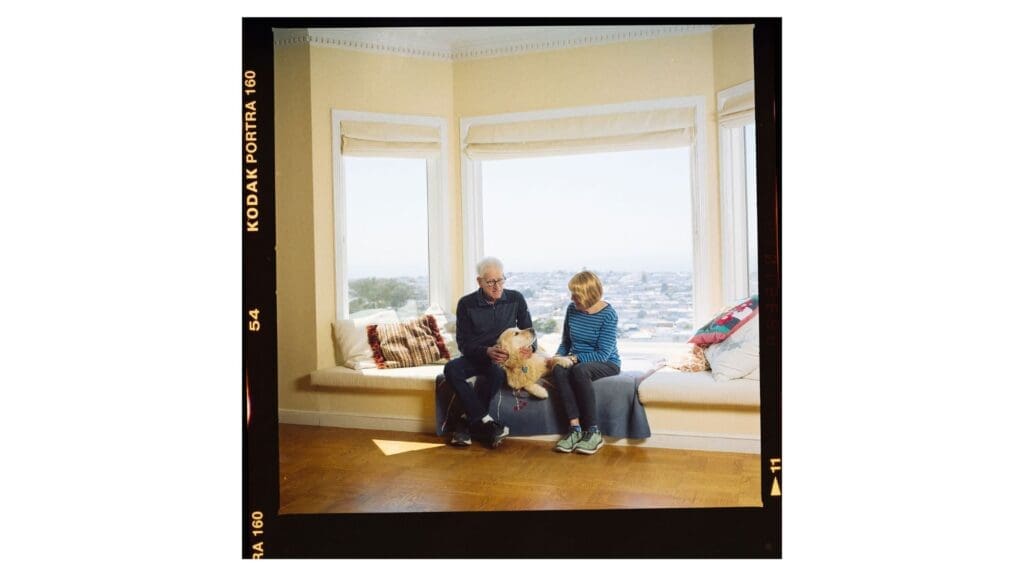

Jim has seen the best and worst of California. He and his wife Leena had a beautiful home in San Fransisco, with a bay window overlooking the Pacific. Meanwhile, Jim would spend hours in a prison or testifying about a homicide that took place at a seedy motel. He found himself in tough positions most people can’t imagine. He once had to do an autopsy on a person he knew, a colleague who was only in his forties when he died. Another time, while his own wife was pregnant, Jim had to do an autopsy on a baby who had died of the mysterious sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Once Jim’s daughter was born, he woke up often at night to check her breathing.

At one point, he was in a group of three pathologists doing autopsies for Napa, Sonoma, and Contra Costa County coroners’ offices. The pathologists called their small group “Casks and Caskets.” Jim would drive an hour and a half through scenic wine country—an area that looks like paradise—to arrive at a small funeral parlor where a body waited for him.

He saw corruption and incompetence in the medical industry: Some doctors were more concerned with building their own fiefdoms and reputations than treating patients. Once, when he did an autopsy on a patient who’d died at a small county hospital, several doctors called Jim to try to influence his findings.

JIM:

No one seemed at all concerned that an error in diagnosis might have led to a death that could have been avoided with proper treatment. They just didn’t want to look foolish or stupid in front of their peer group.

Another time, Jim’s aunt phoned him, desperate because her daughter had recently delivered a baby by Caesarean section at a small Bay Area hospital and the incision was infected. The doctor said he’d done everything he could, but she might die.

Jim called the hospital’s pathologist, who looked at the young woman’s file and told Jim she needed to see the hospital’s infectious disease expert. The obstetrician hadn’t called the expert because they were political enemies. Jim had his aunt ask for a consultation with the infectious disease expert. The young woman survived.

Jim had ignored normal hospital procedure and hierarchy by calling the pathologist. But it was the right thing to do.

JIM:

It just shows, so much of life is like that. You have these rules, but sometimes bad people are making them.

The government has too heavy a hand in the medical industry, Jim says.

JIM:

I think the government—not just with regulating what doctors can do, but by regulating billing and everything else—has really deteriorated the abilities of doctors to get things done. When I started out, I could have my own practice. I could make calls on businesses. And I’ve said that my practice was the last bastion of free enterprise. And it was. It’s gone. I could not do that today. I would have to get a salaried job somewhere and follow a lot of regulations. The government is overregulating. There’s no question that it’s getting much, much worse.

Pacific Legal Foundation now represents several doctors in a lawsuit challenging telehealth restrictions, which make it impossible for patients in states like California and New Jersey to be treated by out-of-state specialists. PLF also successfully challenged a certificate-of-need law that blocked a medical transport company from operating in Kentucky. The government shouldn’t block qualified medical entrepreneurs from meeting demand.

Jim was an entrepreneur in two industries: While working as a pathologist, he was also a landlord—which brought its own eccentricities and struggles.

JIM:

In the early ’70s, my father and I started a real estate business in Los Angeles, owning and managing apartment buildings. I still run that.

Now we’re being creamed by the government. The L.A. Board of Supervisors and state legislators come up with the craziest things and some get passed. It’s ruining private property.

Rent control is a serious problem. I feel that things I own are going to be worthless when I die.

If his daughter and grandchildren didn’t live in California, he and his wife likely would have left the state by now. As it is, they’re leaving San Fransisco to move closer to them in Santa Barbara.

Jim is ready to leave San Fransisco. It’s not like it used to be.

JIM:

People were friendly back then. You could safely walk at night by yourself and it was just like a big playground. And now we feel marooned in our house because we don’t feel safe. And none of our friends do either.

Physically California is still beautiful, but the way it’s run, it’s terrible.

He supports PLF because he believes our cases set crucial precedents for individual rights.

JIM:

A lot of places I’ve supported have great ideas and great talk, but nothing much ever comes of it, as far as I can tell. They talk a good talk, but it’s hard to say what they accomplished.

I think that’s why I came to the conclusion that suing for people’s rights was where I wanted to be.

♦