LISTENING TO POLITICIANS discuss pop culture would be hilarious, if it wasn’t so pitiful.

The 1985 Senate hearings on obscenity in music were a surreal event. Republicans teamed up with Al and Tipper Gore to debate whether pop music was corrupting the country’s youth and whether government should regulate it. The hearings contained the typical politician lectures and bloviations on government’s role in protecting the moral fabric of the country, because, in Al Gore’s words, “It is totally unreasonable, in my view, to expect parents to sit down and listen to every single song in the albums that their children buy.”

But what made the hearings special were the other speakers. Three of the biggest names in music in the 1980s, Frank Zappa, Dee Snider of the band Twisted Sister, and John Denver (a line-up that could only be devised by government), all made their unique case against government censorship. As Frank Zappa eloquently put it, “I am a parent, I have four children, two are here today. I want them to grow up in a country where they can think what they want to think, be what they want to be, and not what someone’s wife or somebody in government makes them be.”

The 1985 hearings were just one chapter in music’s relationship with government censors and our country’s First Amendment freedom of speech, and it was perhaps one of the starkest examples of politicians trying to control the soundtrack of our country’s culture.

Today, that soundtrack is hip hop and rock. Just like in the ’80s, in addition to making influential music, many musicians are being forced to fight the government for their art to exist. Artists like Simon Tam, who is a member of the band The Slants, and rapper Killer Mike have both been involved in recent Supreme Court cases involving artistic freedom of speech and politicians trying to dictate what we’re allowed to hear and say.

What does it mean when the government says you’re racist?

Simon Tam was the plaintiff in the Supreme Court case Matal v. Tam. He argued whether the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office can deny someone a trademark because the government deems that trademark offensive (Tam is Asian American, but the government tried preventing him from trademarking his band’s name The Slants because it said the name was racist against Asians). Tam won his Supreme Court case and set important precedent against government censorship.

“When it comes to freedom of expression and when we’re talking about the First Amendment, we’re really talking about protection against government punishment and government backlash. What does it mean if the government says that your work as an artist is hate speech? What does it mean when the government says you’re racist?”

—Simon Tam

Excerpt from the Supreme Court’s unanimous opinion in Matal v. Tam, written by Justice Alito

Hip hop IS free speech. AKA “You never thought that hip hop would take it this far”

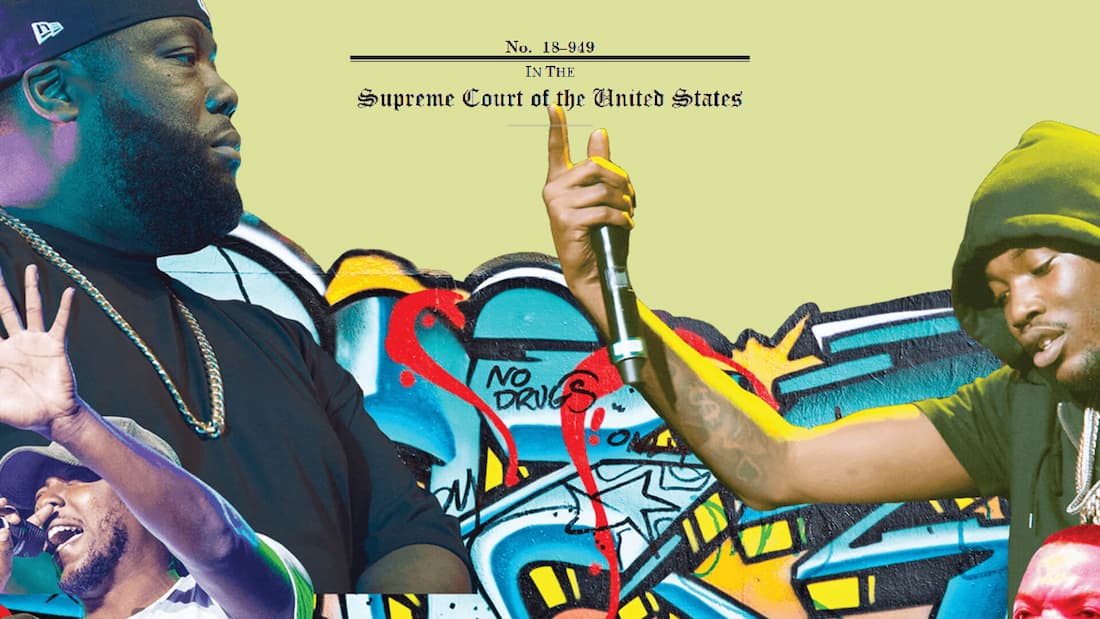

Killer Mike, along with hip hop artists Chance the Rapper, Meek Mill, Yo Gotti, Fat Joe, Mad Skillz, 21 Savage, Jasiri X, and Styles P (along with Simon Tam) filed an amicus brief to the Supreme Court urging the court to take the case Knox v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Knox debated whether a young rapper, Jamal Knox, should be imprisoned for threatening violence by writing a rap song called “F— the Police.”

The excerpt below from the amicus brief filed by these musicians shows how influential hip hop has been to American culture, and many modern views on American freedom of speech.

It is impossible to understand popular culture without understanding hip hop, a cultural movement dating back to the 1970s that is composed of performance arts such as MCing (“rapping”), DJing (“spinning”), breakdancing (“b-boying”), and graffiti (“writing”).

In less than 50 years, hip hop has established itself as one of the most important forms of cultural expression to emerge in modern American history. Today, rap, the musical element of hip hop, is easily one of the most popular genres in the United States. Its sounds and rhythms fill the airwaves, influencing a bevy of genres, including rock, country, and even classical music.

Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Broadway mega-hit Hamilton—a musical about Alexander Hamilton’s life, told in rap form—is a telling example of rap’s capacity to inform and influence popular culture in ways its early creators probably never imagined.

With influence also came critical and scholarly acclaim. Multiple hip hop artists—including Run-DMC, Public Enemy, Tupac Shakur, and N.W.A—have been inducted into the prestigious Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Their lyrics are included in numerous literary anthologies, taught at Ivy League universities, and acknowledged by our most venerable institutions for their imagination, innovation, and sophistication. In 2018, for example, Kendrick Lamar, one of rap’s most commercially successful artists, won the Pulitzer Prize in Music for his album DAMN. The Pulitzer committee dubbed it “a virtuosic song collection unified by its vernacular authenticity and rhythmic dynamism that offers affecting vignettes capturing the complexity of modern African-American life.” Rap’s success helped fuel a multibillion-dollar hip hop industry now seen and heard virtually everywhere—in fashion, film, advertising, politics, and our everyday lexicon.

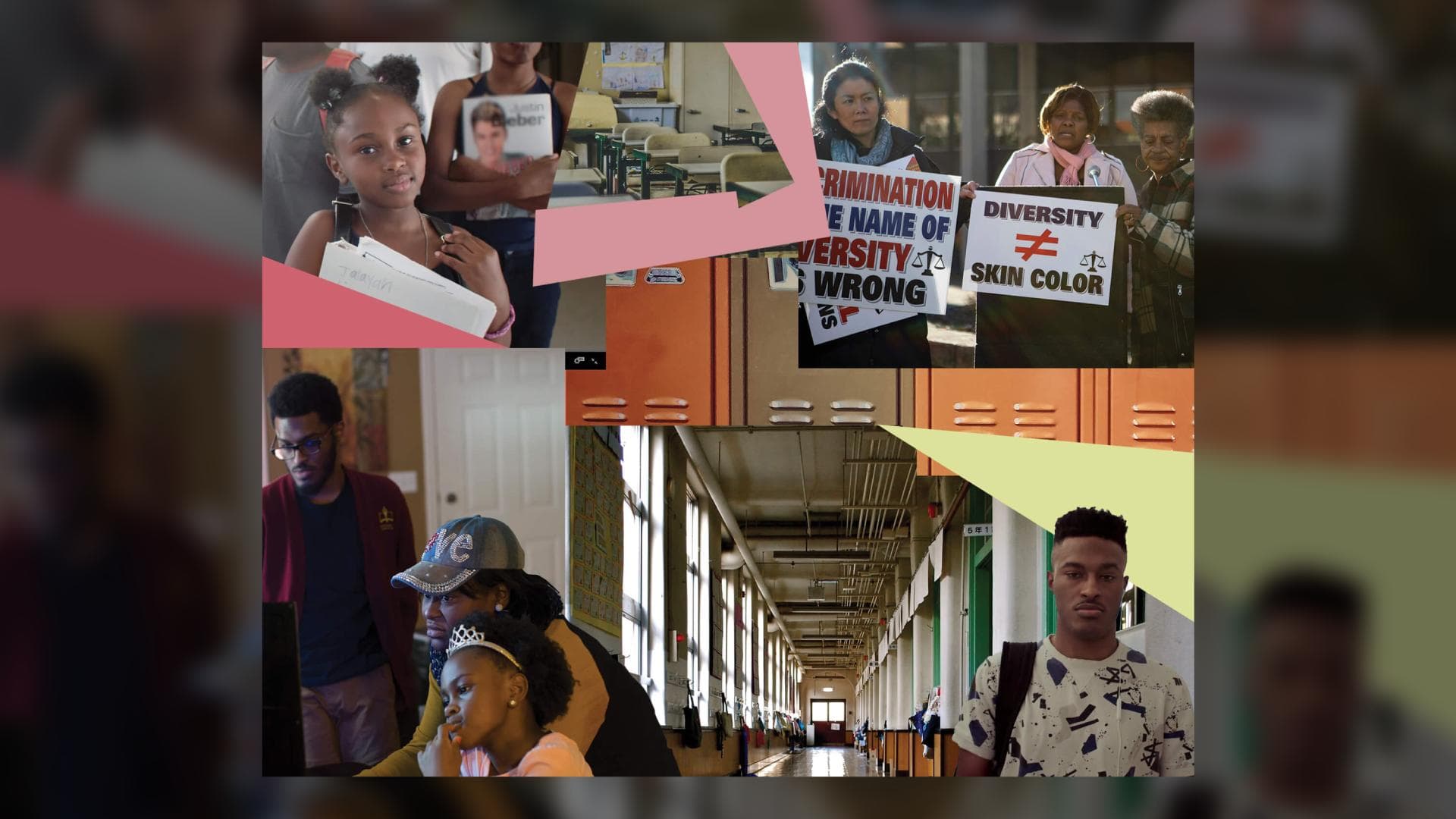

The Supreme Court denied hearing Knox, but the case, along with the amicus brief filed by Killer Mike and the other hip hop artists, forced a national conversation about government censorship, violence, and race that will continue for years to come. Because as these artists’ brief to our nation’s highest court said:

Jamal Knox’s story is not unique. Across the country countless young people—often those of color—have found a voice in rap music, too. For some, it also has offered a legitimate career path, one leading away from the violence and despair so frequently chronicled in rap lyrics. If we criminalize those lyrics, we risk silencing many Americans already struggling to be heard.