IMAGINE TELLING A NINE-YEAR-OLD he can’t continue at his elementary school because of the color of his skin.

That’s a conversation St. Louis mom La’Shieka White had with her son Edmund Lee, not during the Jim Crow era but in 2016. St. Louis policy demanded that black students be treated differently than white students in the name of racial balancing, and Edmund was paying the price.

When you talk to La’Shieka now, in 2023, she seems to smile almost constantly. Life has been good. Edmund is now sixteen and a half and learning how to drive. “We already started doing college visits,” La’Shieka says, shaking her head like she can’t believe it. Edmund is the only kid she knows who thinks high school chemistry class is easy. “It just comes to him,” she says, beaming.

A parent may be forced to explain to a child that, according to the law, their race matters.

But seven years ago, when I first met La’Shieka, she was understandably upset.

What happened to Edmund Lee and his family is a story about good intentions gone wrong. It should be a lesson for anyone who crusades to use the force of government to engineer racial equity: Any time you enshrine racial classifications into the law and dispense opportunities or barriers based on race, you’re creating a situation where a real human being like Edmund will one day be hurt.

And a parent may be forced to explain to a child that, according to the law, their race matters.

Leaving St. Louis

FOR YEARS WHEN EDMUND was young, his stepfather worked as a St. Louis police officer. That meant the family had to live within city limits, which was hard, especially for Edmund and his two younger siblings. They were in a two-bedroom apartment with no yard. Neighborhood crime was on the rise.

“Our kids couldn’t play across the street at the playground,” La’Shieka remembers, “because people would gun the stop sign.”

Shortly before Christmas 2015, someone broke into the family car. That was the last straw. Edmund’s stepfather got a new job, and in the spring of 2016, the family purchased a new home in a leafy suburb of St. Louis. The house had a yard. There were no gunshots.

“We worked really hard to get out of the city,” La’Shieka remembers.

The only drawback to the move, La’Shieka thought at the time, was that Edmund would probably have to leave Gateway Science Academy, the St. Louis charter school he’d attended since kindergarten. Edmund was a gifted kid, and at Gateway, an acclaimed STEM school, he had a 3.8 grade point average. He also had a tight circle of friends. “Kindergarten to third grade, that’s almost your whole little life right there,” La’Shieka muses.

Then, suddenly, it seemed like Edmund wouldn’t have to say goodbye to his Gateway friends after all: Another Gateway parent, whose family was also moving to the suburbs, told La’Shieka that St. Louis County policy allowed suburban students to transfer to city schools. We filled out the paperwork to stay at Gateway, the other parent told La’Shieka. You should too.

La’Shieka was thrilled—until she got the paperwork and read it over.

“I was like: Ohhh. I can’t transfer, but you can,” she remembers.

The other family was white. St. Louis County allowed only white students to transfer from suburban schools to city schools.

And Edmund is black. “I was livid, to say the least,” La’Shieka says.

A Desegregation Policy

BROWN V. BOARD OF EDUCATION ENDED formal segregation of schools in 1954. But in St. Louis, as in many American cities, neighborhoods and public schools remained largely segregated. It wasn’t—and still isn’t—an easy problem to solve. A 2020 Harvard study found that the majority of American parents are in favor of more integrated schools, yet they make personal choices that exacerbate segregation.

In St. Louis, the solution was to carve out a pathway for black city students to transfer into suburban schools while allowing non-black suburban students to transfer into city schools.

Technically, the policy that affected Edmund dated back to 1999; but it came out of a settlement agreement from even earlier, in 1983, before La’Shieka was even born. It didn’t reflect the current realities of St. Louis. “The dynamic is completely different than what it was 30-plus years ago,” La’Shieka says. In 2015, more black families were living in the suburbs; meanwhile some city schools, including Gateway Science Academy, were now majority white.

But the real problem with the policy wasn’t that it was outdated. It was that it entrenched racial identity as the deciding factor in whether children could be enrolled at a school or not. “The goal was to try to balance the racial makeup of the city and county schools,” the Missouri Department of Elementary and Secondary Education later explained in a defensive statement. But racial balancing required giving black and white students different levels of freedom. For Edmund, the policy meant he’d have to leave Gateway… while white peers with the same circumstances, same ZIP Code, would be allowed to stay.

Edmund’s parents had done everything they could to set him up for a bright future— putting him into a charter school, moving him into a safer neighborhood—but because their son is black, they were coming up against a government barrier.

“It wasn’t because we moved. It was simply because of the way that he was born,” La’Shieka says. “And it really put a fire under me.”

She decided to make some noise. She created a petition on Change.org under the heading, “Don’t let race determine my son’s enrollment.”

“Not admitting Edmund simply because he is African American is just wrong,” she wrote in the petition. “We are going to show Edmund that his parents, school, community, and people across the country will fight for what is right.”

Within hours of posting it, the petition had 20,000 signatures.

PLF Reaches Out

IT WAS THE PETITION that brought Edmund’s story to my attention.

La’Shieka started giving interviews about the petition: first to her local Fox affiliate, then to national outlets. The petition grew to over 100,000 signatures.

Lawyers began to reach out to La’Shieka about filing a lawsuit.

“One was like, ‘We’ll charge you $25,000,’” she remembers. “And I’m like, ‘I just bought a home. There’s no way.’”

I sent La’Shieka a letter, explaining that Pacific Legal Foundation was interested in representing Edmund free of charge.

At the time, PLF had never taken on a case involving K-12 education. It’s a fraught area of public policy and law, with competing governing interests and high stakes.

But I’d read Edmund’s story. Here was a clear-cut example of the government treating students differently based on race. Edmund’s parents had done everything they could to set him up for a bright future—putting him into a charter school, moving him into a safer neighborhood—but because their son is black, they were coming up against a government barrier.

La’Shieka answered my letter. Edmund became PLF’s first client in a K-12 discrimination case.

Fighting for Families

IT HAS BEEN SEVEN YEARS since we took on Edmund’s case—a case that we tried, but failed, to bring to the Supreme Court.

For PLF, Edmund’s case opened up a new area of practice. We began representing students and parents in other K-12 discrimination cases: in Connecticut, New York, Virginia, and Maryland.

Not everyone was happy to see PLF representing students like Edmund.

In Connecticut, especially, we faced hostility. There, just as in Edmund’s case, black students were being denied spots at schools because of a desegregation policy. When PLF got involved, the NAACP launched a smear campaign: It circulated a flyer accusing PLF of being “involved with numerous cases that have hurt people of color.” The ACLU accused PLF of trying to preserve segregation. The message to black parents was clear: Stay away from PLF; don’t let them represent you.

As one Connecticut mom, Gwen Samuels, put it: “They were saying there’s this conservative group, they’ve got a hidden agenda.” She added: “I get offended when people tell me that. Because if you say it’s hidden, that means you think I can’t read.” When an NAACP attorney criticized PLF at a panel, another mom, LaShawn Robinson, jumped in: “First of all, we parents hire who the hell we want to hire.”

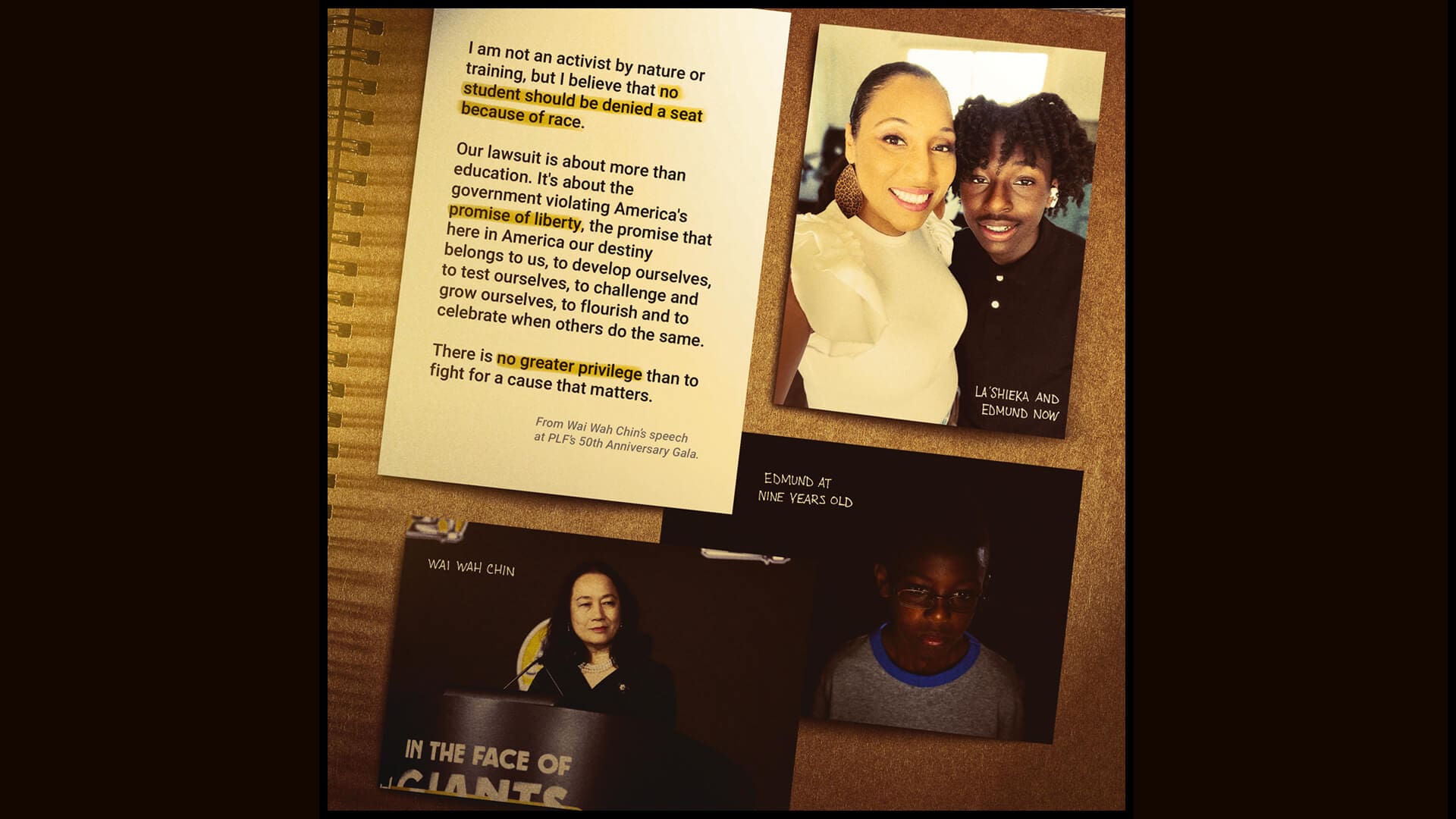

Looking back on her son’s case, the case that started it all, La’Shieka White calls herself “really blessed to get Pacific Legal behind me.” She remembers what it felt like when PLF offered to work with her family:

Here we are, just moved into our new house. We’re worried about how we’re going to deal with this huge issue. We maybe don’t have the money to do it. You feel less-than. Then here you guys come, saying, ‘Hey, we’ll pick up some of the pieces if you fight with us.’ It helped me realize that my voice is so much more powerful than what I think.

The Result of the Case…

WE LOST EDMUND’S CASE IN COURT. But the court eventually clarified that charter schools like Gateway Science Academy would be exempt from the desegregation policy going forward.

Edmund left Gateway Science Academy while the case was being litigated and has been attending school in his local suburban district. He missed Gateway’s rigorous schedule, but he made new friends and continued to excel. What happened to him as a third-grader made an impression on him—in a good way. He saw his mom stand up for his rights. Now that he’s a teenager, his friends sometimes Google his name and stumble onto the case. He’s even had teachers discuss the case in history class. Edmund answers their questions, telling them what it felt like when he and his mom were doing interviews together, speaking about equality under the law.

As for La’Shieka, even though the lawsuit didn’t end in a legal victory, she recognizes the effect of her son’s case on other families. She says, “I really feel like we opened the door for people to say, ‘Hey, I think PLF can help us, and I think we can win.’”