CALM AND COLLECTED, Ward Connerly sat before the Senate Judiciary Committee in 1996, where he had been summoned to give testimony in favor of the passage of Proposition 209—a California initiative that would end racial—and sex-based preferences in public schools and government institutions.

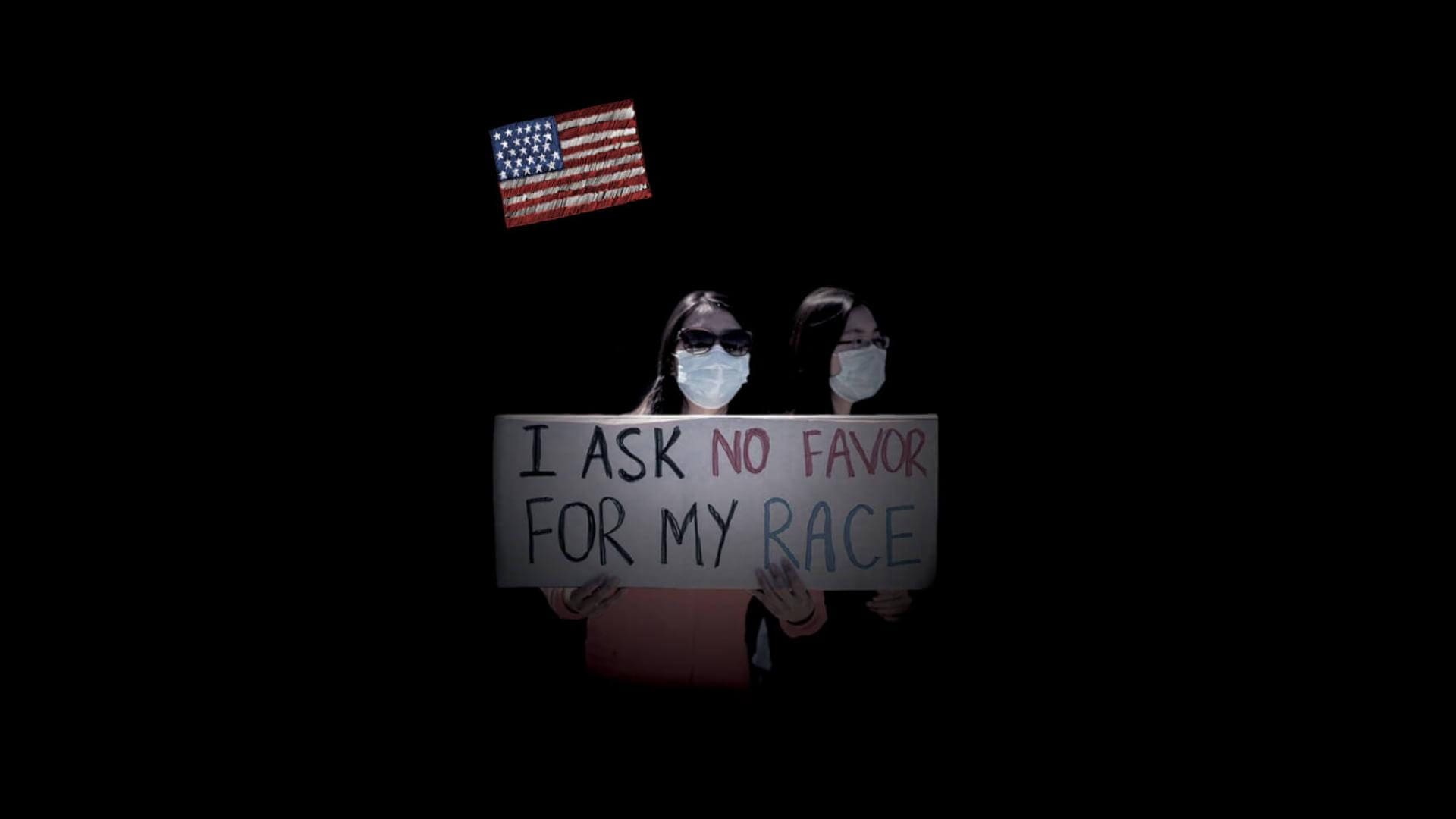

In the 1990s, it was an odd sight to see a black man standing in front of lawmakers asking them to reject the notion of racial quotas. But Connerly never made a habit of forming his views based solely on the color of his skin. As a staunch individualist and a believer in the constitutional guarantee of equality before the law, he stood on principle first and asked for no favors because of his race.

“When I pledged allegiance to the flag, Senator, it was engrained in me that the goal of this nation is to become one nation and one people without divisible parts. And that liberty and justice was for all, not with some parenthesis added—white, black—but for all,” he spoke unflinchingly as senators listened.

Connerly believed in the individual-centered civil rights movement for which Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and other freedom fighters had fought so fervently. He believed that equal, not preferential, treatment was the key to overcoming racism. But over time, the movement he wholeheartedly supported had been distorted, as many were now seeking the latter.

“There are those who say that we must use race to get beyond race. I disagree. The use of race is not inoculating us from the virus of racial hostilities. It is becoming the cause of the infection. And we must cure the problem.”

He continued: “The time has come for us to eliminate government programs and concepts that legitimize treating our citizens differently based on immutable traits.”

Powerful words from a brave man who never yielded or compromised his sense of purpose in pursuit of a worthy goal, even when doing so might have been the easier path.

While many applauded his commitment first to principles, there were also those who believed he was turning his back on the black community. His work in this arena even earned him the title of “the most hated Black man in America,” as one Sacramento news outlet described him. Another newspaper featured political cartoons where Connerly was depicted standing next to Klansmen—his alleged allies.

But his determination to do the right thing started long before he testified in front of Congress that day in 1996, and it would continue long after.

Born with a “C” on his birth certificate

CONNERLY’S CRITICS WOULD often try to paint him as a man of great privilege. But his childhood was anything but.

Born in Leesville, Louisiana, in 1939, his birth certificate was branded with a large letter “C”—not for his surname but designating the newborn as “Colored.”

His father left the family when he was only two years old and his mother died two years later of a brain tumor. In 1947, he went to live with his widowed maternal grandmother, also located in Leesville.

While his grandmother tended to the diner and bar she inherited after her husband died, young Connerly worked odd jobs to help her with household expenses.

His grandmother taught him to work hard, to treat every person the way you wanted to be treated, to be fair and honest, and to believe in the good Lord.

When he was a teenager, Ward’s grandmother sent him to live with his aunt and uncle in Washington state to get him out of the South. Eventually, Aunt Vern and Uncle James moved to Sacramento, California.

For any child, moving around can be tough. But he never let his family life impact his present or future. He believed that through hard work, anything was possible, a lesson that was solidified by his Uncle James, who became something of a mentor to the young boy. Despite his uncle’s inability to read or write, he made an honest and decent living as a lumber stacker, and the couple even owned their own home.

James gave Connerly three rules to live by: “My shoes had to be shined, the lawn had to be mowed, and the car had to be clean. He taught me to have pride in myself.”

Understanding all too well the hurdles black men had to face in society, James instilled in him the importance of education. “You’ve got to get an education, they can’t take that away from you,” he always said.

A bit later, when his grandmother relocated to Sacramento, she wanted her grandson to come live with her again. Connerly had grown comfortable in his aunt and uncle’s middle-class lifestyle, where he even was given $5 of spending money every now and then. Life with his grandmother was an economic downgrade. She often couldn’t afford to pay her $35 mortgage, and nightly dinners consisted only of sweet potatoes. Things got so dire, Connerly had to slip cardboard into his shoes to conceal the holes in the soles.

Self-reliance was important to the family. When hardship fell upon them, they turned to their church and not the government. When his grandmother had no choice but to seek government assistance, she did so with great shame.

Connerly had gone from a nice home and an allowance to living on the brink of poverty, but he was committed to rising above his circumstances, and he knew college was the right path to achieving his ends.

In 1962, he earned a degree in political science from Sacramento State College, where he was one of about 50 black students on a campus of 2,000. Active in campus life, he served as student body president and blazed a trail by joining a white fraternity. As Connerly puts it, “If I can make it, anyone can.”

Even during a tumultuous time for race relations in America, his experience in college is where he strengthened his beliefs in the importance of the individual. He never felt like race held him back as a student, and he never felt like he didn’t belong.

But while he may have made it out of the Deep South at an early age, he was the product of decades of racial discrimination. The government’s role in perpetuating racism was not lost on him. But he did not see further government action as the solution. Instead, he focused on bettering himself to make the world a better place—a theme that would continue throughout his entire life.

As he came of age, the civil rights movement was at its height, and he became an admirer of Dr. King. He believed that equality was not to be found by using the tragedies of the past to gain special privileges.

“You can’t un-ring the bell on slavery. All you can do is make sure the next person who walks through the door, white or black, receives equal treatment.”

Getting in the arena

THE SPARK THAT fueled Connerly’s lifelong work on equality before the law was lit during his college years. He had befriended a fellow student who had moved his wife and children from Iran to study abroad.

His friend had tried desperately to secure housing across the street from campus, but he was repeatedly turned down because of the color of his skin. Unable to find housing for his family, his friend had to commute to campus each day on his motor bike. He was later killed in a traffic accident. Connerly knew that if he had been allowed to live closer to campus, he wouldn’t have been killed.

This devastated Connerly, who took up the cause of housing discrimination in his late friend’s honor. After his friend was killed, he testified before the California legislature arguing for civil rights legislation that would prevent landlords from discriminating against potential tenants because of their race.

He later took a sociology class from a professor named Dr. Record, whom Connerly describes as a “real civil libertarian.” This is where his views on the world really started to take shape. Record never focused on the collective—instead, he believed in the individual.

It was through his guidance that Connerly realized that as badly as he wanted to end discrimination and protect the Fourteenth Amendment’s promise of equal treatment, government could not be the hero. The Constitution promises equal opportunities for people to better their lives through merit, not a guarantee of success because of skin color.

This was the foundation on which he built his political career, and he spent much of his young adult years fighting for equal housing opportunities.

His work on housing caught the attention of Pete Wilson, a California state senator who would later become the mayor of San Diego, a United States senator, and eventually the governor of California. After Wilson became governor, he offered Connerly a position on the University of California Board of Regents. Connerly didn’t really want the position (during his Senate testimony, he would joke that he “would never forgive” Wilson for appointing him to the Regents). By this time, Connerly had a successful consulting firm and a happy life, and joining the Board of Regents was a volunteer position with a lot of stress and little upside.

But as many friends are, Wilson was persuasive and convinced Connerly to take the role. It was a decision that would change Connerly’s life—and California forever.

Fighting discrimination, no matter what

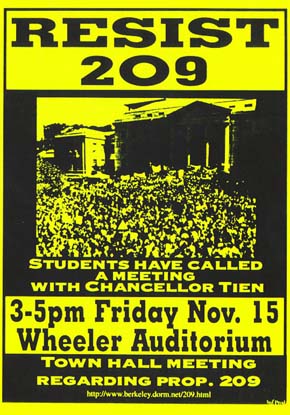

IN THE LATE 980s and early ’90s, equity in college admissions had become a focal point across the country, especially in California. When Connerly joined the UC Board of Regents, he began visiting campuses and analyzing admissions data to learn more about how the schools were operating and what he could help improve. What he found went well beyond simple bureaucratic fixes. Connerly discovered that administrators across every school in the University of California system were racially engineering the student body to ensure they had the “right” number of students of every race—and the ethnicity at the bottom was Asian-Americans.

When he went to the Board of Regents with his concerns, he didn’t realize how much he had rocked the boat. As Connerly describes it, “When I discussed this discrimination with faculty members and the UC administration, basically they said, ‘We just have to build diversity. We have to celebrate our diversity. If we didn’t do that, Berkeley would be all Asian.’”

That wasn’t acceptable to Connerly, though, so he introduced two resolutions to the school’s governance policies that would end all racial profiling in college admissions. Most of the other Board of Regents members were scared of Connerly’s resolutions. None of them wanted to be branded racist. Some even went to Wilson asking that Connerly be silenced. But Wilson supported his friend, and Connerly stayed on the Board and the resolutions passed.

Now it was time to end discrimination at a state level.

Connerly and Wilson both believed that discrimination was wrong and had no place in state laws or policies. So Connerly started campaigning for an amendment to the California Constitution that would ban any discrimination based on race, sex, or any other immutable characteristics.

The fight for Proposition 209 had begun.

This was when he first found himself in the crosshairs as a target of criticism from the civil rights establishment, media, and other defenders of the status quo.

“I started really getting the heat from the ‘black community,’ of which I am a member by reason of my societal designation,” he says. “But I don’t pretend to represent anybody—black, white, purple, whatever. And so I was an outsider. And I’d be sitting in a meeting, in an airport or someplace, and I’d be recognized and viewed with contempt. And bullet holes, BBs I’m sure, were shot through the glass at my office. It was a tough time, because I was branded as a traitor—someone who was hurting black people.”

Rev. Jesse Jackson attacked him, denouncing him as a “house slave” and a “puppet to the white man.” Likewise, Al Sharpton cast his own stones at Connerly, asserting that he was not a true civil rights defender.

“I don’t care how much you pride yourself on being an individual, you always wonder about whether you’re doing the right thing or not,” Connerly says. “You can’t avoid that. Those were some of the most difficult months of my life, because I had to examine my own strength of character. How willing would I be to stand up against what I knew was happening?”

Emotionally taxing as this may have been, he remembered the advice one of his mentors had given him when he first got involved in politics.

“Mr. Connerly, consult your knower. There are certain things that you will do in life, and you won’t be able to rationalize it intellectually. But you just know that you should do it. You just know.”

Leading up to his 1996 Senate testimony, he had gone up against a well-funded campaign to defeat Prop 209 led by the state Democratic political machine; liberal advocacy groups; teachers’ unions and other organized labor organizations; the civil rights establishment; and the entertainment and media industries.

But he always consulted his “knower” and pressed on. Connerly travelled around California to spread the word on Prop 209 and tried to elevate it above the typical political fray of Republican vs. Democrat—after all, equality before the law should be a bipartisan goal.

Finally, after months of discussion, debate, and campaigns on both sides all over the state, Proposition 209 passed with a decisive 55% of the vote.

While his critics cried wolf about the “inevitability” of Proposition 209 harming minorities, data regarding college admissions has shown the opposite result.

The University of California’s own research has found “no evidence that yield rates fell for minorities relative to other students after Proposition 209, even after controlling for changes in student characteristics and changes in the set of UC schools to which students were admitted. In fact, our analysis suggests Proposition 209 had a modest ‘warming effect.’”

Even though he often felt like he was standing alone, he knew that supporting Proposition 209 was the right thing to do, and history has validated his beliefs.

But the fight wasn’t over yet.

The fight continues

DESPITE THE INCREDIBLE impact Prop 209 had in California, activists throughout the years have tried to challenge it in court. Pacific Legal Foundation worked with Ward Connerly to defend Prop 209 in multiple cases. Then in 2020, many of the same activists who opposed Prop 209 in the ’90s sought to reverse it with Proposition 16.

When Prop 16 made it on the ballot, Connerly got another call from his old friend, Pete Wilson. Wilson told Connerly how Prop 16 was putting everything they fought for with Prop 209 at risk, so once again Connerly campaigned all across California against discrimination and for race-neutral laws and policies. Discrimination, Connerly once again explained, no matter how supposedly well-intended, is wrong.

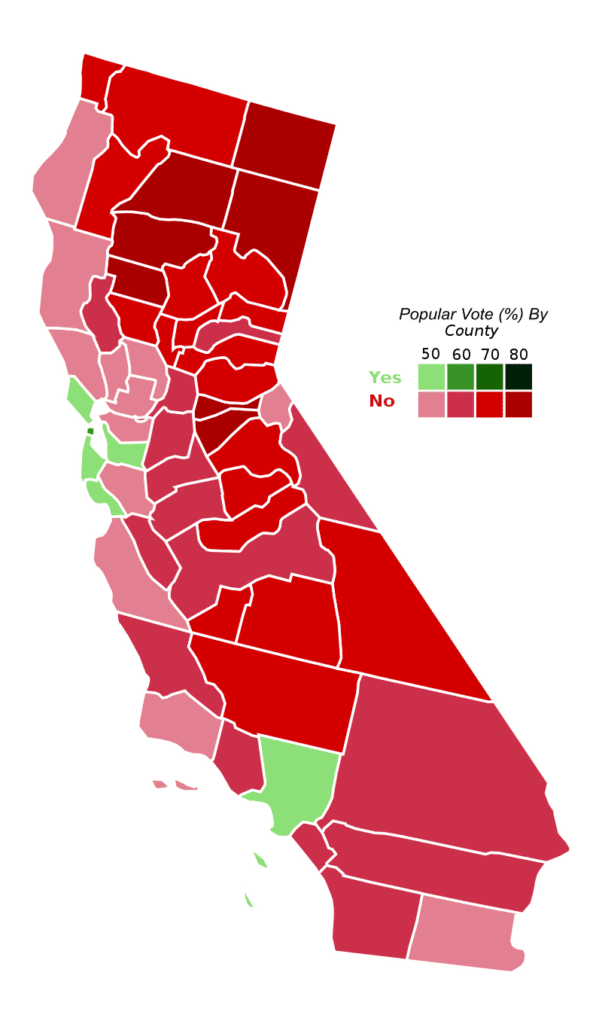

2020 Election Results for Prop 16

Fortunately, Californians listened, as voters said “no” to Proposition 16 and supported true equality.

Connerly’s entire political career had led him to this moment. For decades, he had focused on the broader conception of civil rights that places primacy on individual liberty, rather than on preferences for designated groups. And last year, he came out of the fight victorious.

But Connerly’s push for equality does not end with race. He applies that broad equality principle consistently—it led him to become a supporter of equal benefits for domestic partners regardless of sexual orientation, a position that placed him at odds with some of his conservative allies. As always, he stands for principles first.

Now 82, Connerly’s life is a case study in how to stand up against injustice. It takes an unwavering belief in the individual, dedication to the constitutional guarantee of equality before the law, and—above all—the guts to stand up for what’s right in the face of great opposition.

While the struggle for equality is never-ending, we can look to Ward Connerly as a true hero of the modern civil rights movement.