“I HAVE A SEARING memory of a day in my childhood.”

William Leuchtenburg was a boy living with his family in New Jersey during Prohibition. His father, a postal worker, commuted into Manhattan to work at a post office near Penn Station. But Mr. Leuchtenburg’s salary was modest, so he supplemented the family income by running a small still in the basement of the family home and selling his liquor locally.

Eight-year-old William was sitting on the front steps of his home one day when two strange men in suits arrived to speak with his father.

“They know he has a still in the cellar. And he has to smash it,” William, now a historian, recounts in Ken Burns’ documentary miniseries Prohibition. “And that takes away the extra family income. We are forced to move into the borough of Queens in New York—to give up the house, the countryside. And the city, and life, close in around me.”

“Virtually every part of the Constitution is about expanding human freedom, except Prohibition, in which human freedom was being limited.”

Pete Hamill

For middle- and working-class Americans, this was what 1920s Prohibition meant: It meant the loss of choice and opportunity—the forced shuttering of economic freedom. Thousands of people lost their livelihoods: not just distillers and saloon workers, but also truckers and barrel-makers.

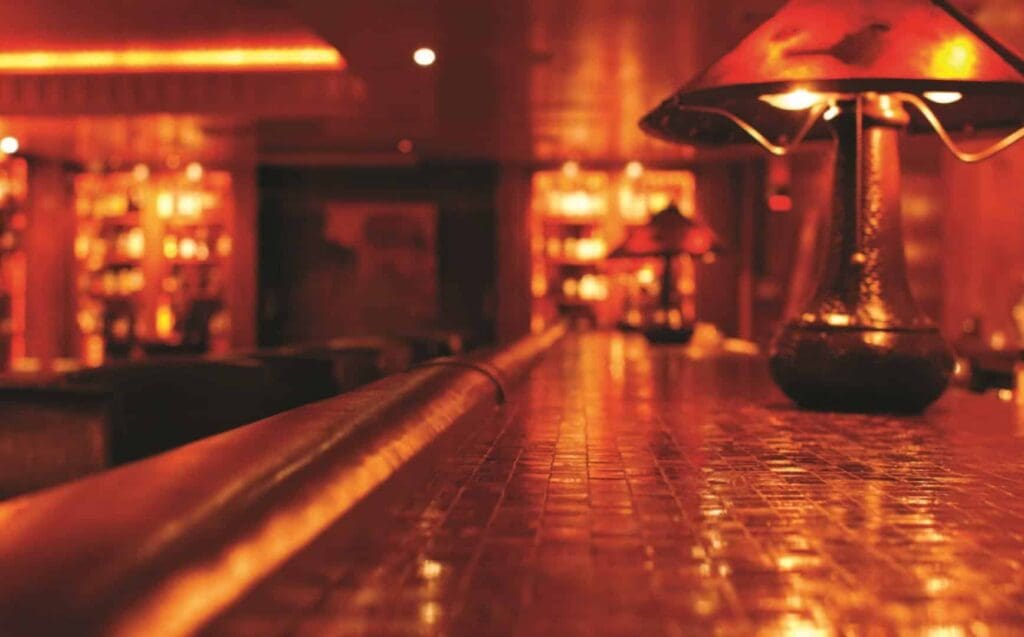

And yet, on those same nights that young William Leuchtenburg was huddled up in Queens, feeling life close in around him, Manhattan’s glitterati were drinking and dancing in speakeasies until morning. An estimated 30,000 speakeasies operated in New York City by the mid-1920s, fueled by liquor that had been bootlegged, smuggled, and hoarded.

“You pass the portals of a guarded house, leave the throngs in the Avenue, and straightway you are transported to another clime,” travel writer Stephen Graham wrote in New York Nights, his 1927 guide to New York speakeasies. “Inside is all unreality, sentiment, indulgence and relaxation.”

For anyone with money and social connections, this was what Prohibition meant: raucous nights in pop-up clubs tricked out in lush, theatrical decorations—silver Venus de Milos, painted lanterns, cigarette girls in Russian costumes—where well-heeled clientele paid a “couvert charge” to drink and socialize with other privileged, in-the-know sophisticates.

But what about the working class? The saloonkeepers who lost their livelihoods in 1920 when the Eighteenth Amendment went into effect? The farmers who could no longer distill surplus crops?

They bore the cost of Prohibition—while the elite danced.

What working America lost

BEFORE PROHIBITION, distillers, brewers, and barmen held a place of distinction in American society.

Whiskey was a financial lifeline for farming communities.

George Washington became a successful distiller after leaving the White House. The early Supreme Court often met in a tavern. Abraham Lincoln sold whiskey at a Kentucky tavern before becoming a lawyer. (When Stephen Douglas pointed out that fact during their 1858 debates, Lincoln replied, “It is true that the first time I saw Judge Douglas I was selling whiskey by the drink. I was on the inside of the bar and the Judge was on the outside. I was busy selling, he was busy buying.”)

Whiskey was a financial lifeline for farming communities. Farmers didn’t have to waste corn, rye, and wheat that would soon rot—instead, they could distill it into whiskey, which was easier to transport than raw crops. In rural communities without reliable banking, whiskey could even be used as a form of currency.

And the saloon was a form of community center: According to a union worker in 1900, saloons were “looked upon by the vast majority of workingmen as their club.” In Irish, Scandinavian, and Italian immigrant neighborhoods, saloonkeepers provided job opportunities and advice to their fellow immigrants. In factory towns, a saloon would sometimes become a “poor man’s bank” where workers could cash their paychecks with the saloonkeeper. In other words, saloons were the ideal “third place” for working Americans: a regular spot they could visit between work and home, where they’d find comfort, connections, and a much-needed sense of belonging.

“Saloonkeepers are notoriously good fellows,” Jack London wrote in 1913. While traveling, London made a practice of visiting a saloon in a new town, buying the saloonkeeper a drink, then asking for travel advice. “I was no longer a stranger in any town the moment I had entered a saloon,” London wrote.

The Eighteenth Amendment

EVERYTHING CHANGED on January 16, 1919, with the ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment.

The amendment declared that one year after ratification, “the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors” would be prohibited in the United States.

“Virtually every part of the Constitution is about expanding human freedom,” writer Pete Hamill muses, “except Prohibition, in which human freedom was being limited.”

Congress also passed the Volstead Act, which implemented the fine details of the alcohol ban. As of January 17, 1920, Prohibition was enforceable law—which meant workingmen lost their saloons, and honest businessmen suddenly became criminals.

“I’ll give you bartenders forty-eight hours to quit your jobs and get away from the saloon business,” a Prohibition agent threatened in The New York Times.

Prohibitionists had a paternalistic attitude about the law’s effect on the working class: They believed the alcohol ban was a benevolent law that would save men from themselves, forcing them into more productive vocations and habits. Among the loudest cheerleaders for Prohibition were eugenicists, who believed Prohibition was key to engineering more perfect human beings.

Some temperance advocates were convinced that Prohibition would be the dawn of utopia in America. The day after the Eighteenth Amendment went into effect, evangelical preacher Billy Sunday threw a mock funeral for “John Barleycorn” (a personification of alcohol) and declared: “The slums will soon be only a memory. We will turn our prisons into factories and our jails into storehouses and corncribs.”

But Prohibition didn’t end poverty or crime; it simply pushed some distillers into the black market, where they either got caught by Prohibition agents or found success as criminals. Others gave up. Restaurants that played by the rules struggled to make a profit without liquor sales. Many failed, leaving servers and cooks scrambling for new jobs. By the mid-1920s, anti-Prohibition congressmen estimated that Prohibition had destroyed 100,000 jobs and cost a billion dollars in closed businesses.

An industry that had been a source of economic opportunity for over a century was suddenly in exile—and organized crime had taken over alcohol production, bringing new violence to America’s streets.

Speakeasies replace saloons

WHILE WORKING AMERICANS were losing jobs and struggling with rising crime, the wealthy were finding loopholes in the law—or flat-out ignoring it.

“I don’t know how you fellows feel about Prohibition,” one gin-drinking character says in Sinclair Lewis’ 1922 novel Babbitt, “but the way it strikes me is that it’s a mighty beneficial thing for the poor zob that hasn’t got any will-power, but for fellows like us, it’s an infringement of personal liberty.” Another character says that Prohibition is fine—“for the working-classes.”

Babbitt was satire, but Lewis was capturing a real feeling among the upper classes: that Prohibition was for other people.

Americans with money, power, or social influence could keep right on drinking. It was technically legal to consume any alcohol that you had purchased before Prohibition went into effect—and because the Eighteenth Amendment went into effect a full year after it was ratified, savvy Americans with means had a full year to stock up on supplies. The Yale Club in Manhattan was rumored to have stocked up so much liquor in that year that they were able to serve their club members for the entire 13 years of Prohibition.

Any well-connected American who didn’t stock up on liquor could finagle a doctor’s prescription for whiskey: Prohibition laws had a loophole for “medicinal” alcohol, and some distilleries successfully lobbied Congress to be licensed for medicinal purposes. Doctors earned an estimated $40 million writing whiskey prescriptions during the 1920s.

The wealthy took advantage of all loopholes in the law—but they barely needed to. They were never the real targets of Prohibition. Enforcement was unequal by design: The saloons that catered to factory workers were forced to close, and middle-class families were punished for home-brewing; but law enforcement was less interested in interrupting the parties of fashionable society.

“The speakeasy has replaced the saloon,” John D. Rockefeller wrote in 1932. Barrooms that served the working public had shuttered, but decadent speakeasies and clubs flourished.

And for the chosen few, the ’20s roared.

“Washington ought to be dry. But shucks. The city’s so wet that it squishes.”

Collier’s Weekly, 1929

When The New Yorker began weekly publication in 1925, it included a regular column on the nightclub scene by a Vassar-educated 23-year-old named Lois Long, who wrote under the nom de plume “Lipstick.”

“Will somebody do me a favor and get me home by eleven sometime?” Long cooed at the end of one column. “And see that nobody gives a party while I am catching up. I do so hate to miss anything.” In another column, she described a waiter inviting couples to a “Wee Hours Club” in a converted brownstone. “Many big dancing places maintain a whole string of these tiny places to make the hours between one and eight in the morning more exciting,” she wrote.

The hypocrites in Washington

NO ONE CAN BLAME young Lois Long for making the most of the Prohibition era. But what about the power brokers of Washington, DC—the city responsible for passing and enforcing Prohibition?

“Somehow, it doesn’t seem right,” laments a 1929 article in Collier’s Weekly. “Of all cities, Washington, where all the Prohibition laws are passed and millions of dollars appropriated to exterminate the liquor traffic—well, Washington ought to be dry. But shucks. The city’s so wet that it squishes.”

Garrett Peck’s book Prohibition in Washington, DC: How Dry We Weren’t vividly recreates 1920s drinking culture in the nation’s capital.

“Washington was to be the model city for the dry cause,” Peck writes. The capital technically banned alcohol two years before the Eighteenth Amendment passed. “But Congress was never dry, even if it voted that way. The U.S. Capitol sat on a hill of hypocrisy.”

Not only did congressmen drink, they also made special allowances to help their friends drink.

Congressmen who had publicly voted for the Eighteenth Amendment and the Volstead Act—putting honest saloonkeepers, distillers, and brewers out of business—seemed to have no compunction about indulging privately in bootlegged liquor and speakeasies. The Capitol City Club on U Street NW was one of many members-only clubs that could be accessed only with a key—keeping policemen and the public out.

But congressmen also drank in their offices. “It is hardly necessary for even the most impassioned dry congressman to pull down the blinds in Washington when he wants to wet his whistle,” journalist Raymond Clapper wrote in 1927. “The Prohibition agents there all have very poor eyes.”

In 1930, bootlegger George Cassiday outed Congress’ booze-buying habits in an explosive series of Washington Post articles. “For nearly ten years I have been supplying liquor at the order of United States senators and representatives at their offices in Washington,” Cassiday wrote in his first article. “On Capitol Hill I am known as ‘The Man in the Green Hat.’ […] It may be a surprise and a shock to many good people to know that liquor has been ordered, delivered, and consumed right under the shadow of the Capitol dome ever since Prohibition went into effect.” Cassiday informed readers that approximately four out of five congressmen were drinkers.

Not only did congressmen drink, they also made special allowances to help their friends drink. When President Woodrow Wilson moved out of the White House in 1921, he wanted to take his extensive wine collection with him. But the Eighteenth Amendment forbade the transportation of alcohol—so Congress passed a special law giving Wilson permission to take the wine to his new DC townhome.

President Warren Harding, who moved into the White House the same day Wilson moved out, didn’t even bother asking Congress for special permission—he just brought his liquor supply with him. At the Harding White House, Peck writes, “whiskey flowed freely.”

Prohibition permanently changed individuals’ relationship to the federal government.

Bootleggers who faced jail time argued that the government was full of hypocrites. “Why, the very guys that made my trade good are the ones that yell loudest at me,” gangster Al Capone complained after one of his jail stints. “Some of the leading judges use the stuff.”

As for the federal enforcement agents tasked with keeping the country dry: So many of them were fired for accepting bribes that the Department of Justice had trouble keeping the unit fully staffed.

A century later

PROHIBITION LASTED “thirteen awful years,” as Baltimore journalist H. L. Mencken dubbed the period. Congress finally repealed the Eighteenth Amendment on December 5, 1933.

But Prohibition’s effects on the country continued long after repeal.

Americans who’d lost businesses, livelihoods, and income weren’t able to make up for what they’d lost. Pre-Prohibition saloons—workingmen’s clubs—couldn’t be revived.

Young William Leuchtenberg could hardly rewind and reclaim the childhood in the country he would have had if enforcement agents hadn’t closed his father’s still.

Prohibition permanently changed individuals’ relationship to the federal government. It set an alarming precedent: The government could decide to criminalize your business or occupation, pushing you out of the life you’d built for yourself. Many Americans viewed the government with new wariness.

“They lust to inflict inconvenience, discomfort, and, whenever possible, disgrace upon the persons they hate,” Mencken fumed about Prohibitionists, “which is to say, upon everyone who is free from their barbarous theological superstitions, and is having a better time in the world than they are.”

The government—despite its clear failure to achieve the goals of Prohibition—was emboldened to continue intervening in individuals’ choices. Prohibition “pushed the federal government in the direction of policing and surveillance,” says Lisa McGirr, Harvard professor and author of The War on Alcohol.

For “thirteen awful years,” the government cracked down on the economic freedoms of working Americans, while people with social or political power skirted authorities and kept on drinking. Prohibition provided a grim lesson for America that remains true to this day: When the federal government enacts sweeping laws that curtail economic liberty, the laws won’t be felt equally. Well-connected groups will still get their speakeasies and whiskey prescriptions—while working Americans feel the grip of federal regulation close in around them.

GIN RICKEY

Lobbyist Joe Rickey invented the bourbon rickey in the 1880s in Washington, DC. This gin version, created about a decade later, quickly became the more popular iteration and was a mainstay cocktail at Prohibition-era speakeasies. DC mixologist Derek Brown calls the drink “air conditioning in a glass.” In F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925), Tom Buchanan serves gin rickeys “that clicked full of ice” on the warmest day of the summer. (Incidentally, blue-blood Tom derisively accuses Jay Gatsby, “Mr. Nobody from Nowhere,” of being a bootlegger—yet Tom clearly has no compunction about drinking gin rickeys. Prohibition is not for people like Tom.)

To make your cocktail: Squeeze and drop half a lime into the glass. Add 2 oz of gin, then add ice. Top with club soda and stir gently.

2 oz gin

Sparkling water

Half a lime

Ice

Highball glass