About 15 miles from the old Scotch Lumber Mill in Clarke County, Alabama, is a stretch of pine forest that was once open to the public.

The family that owns the land—and back then, owned the lumber mill—established it as the Scotch Wildlife Management Area in 1952 and opened it for public recreation and conservation. Four years later they began allowing public hunting, all the while continuing to manage the land productively as a working forest to produce sawtimber.

“Whenever someone’s putting rules on us, prohibiting our ability to manage our land for generations, that does not sit well with us.”

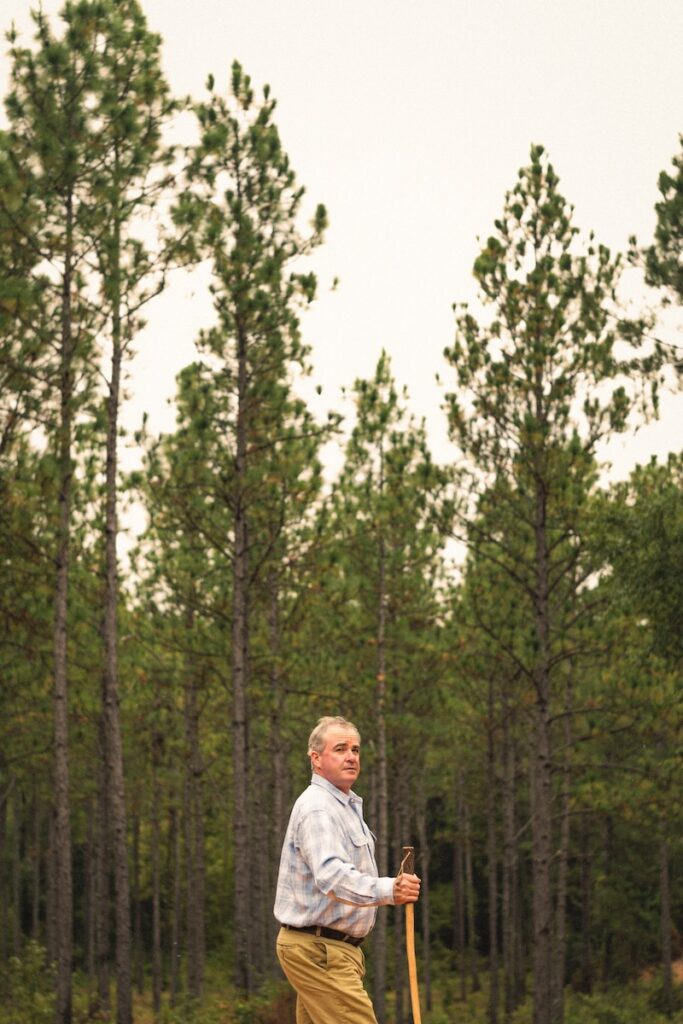

Gray Skipper

The area is rich and green: It’s where locals once allowed free-range cattle to graze. (Free-range cattle were outlawed in the early fifties, explains Gray Skipper, whose extended family owns the land. “You could own your cattle, but you couldn’t run it across everybody else’s land anymore.”) Gray’s family took good care of this land, using prescribed burns and selective thinning to turn it into a thriving and diverse forest ecosystem. But it’s no longer the Scotch Wildlife Management Area. The family was forced to close the area down.

“We ask those who have enjoyed the use of this land to consider the fact that we were led to this action only by what we regard as environmental regulatory overreach by the federal government,” Gray said in a public statement. He added:

For almost 60 years, our family-owned timberland has provided public access. We would have been happy to continue to do so for another 60 years, if it were not for government action that threatens our use of the land.

The ‘Threatened’ Snake

The black pine snake is a large, muscular constrictor. It can grow up to six feet long and burrows underground in its habitat: the pine forests of Mississippi, Louisiana, and Alabama.

The snake is not endangered. But in 2015, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service concluded the snake was likely to become endangered—so the agency listed the snake as a “threatened” subspecies under the Endangered Species Act.

It was the listing that spooked Gray Skipper’s family. If a threatened species is allegedly sighted on your property, it’s game over: You lose the legal ability to use your land the way you want. It’s regulatory quicksand, holding you down, sinking the value of your property.

“Whenever someone’s putting rules on us, prohibiting our ability to manage our land for generations, that does not sit well with us,” Gray says.

With the threatened listing hanging over Alabama pine forests, the family felt they had no choice: They closed the Wildlife Management Area in 2016. It’s hard to invite strangers onto your land—including government officials—knowing any reported sighting of a snake could be devastating.

“How can we stay in the [Wildlife Management Area] and partner with government officials?” Gray told Farm Journal. “I have to guess that if we let them stay on our land, they’ll declare protection for other animals that aren’t there either. The more they do it, the less useful our land is, and this is a working forest.”

But the closure came too late. In 2020, federal officials designated more than 10,000 acres of the Skipper family’s land as a critical habitat—based on a single sighting of the black pine snake, the only sighting in 25 years. The boundaries of the habitat roughly matched the boundaries of the now-shuttered Scotch Wildlife Management Area. It was as if federal agents looked at a map and figured, Wildlife Management Areas might as well be ours.

“No good deed goes unpunished,” Gray told Farm Journal. “Where has reason gone in this country?”

Putting Up Walls

In Robert Frost’s 1914 poem “Mending Wall,” two neighbors examine a broken wall that divides their two properties. The narrator wonders why they need a wall at all:

He is all pine and I am apple orchard.

My apple trees will never get across

And eat the cones under his pines, I tell him.

He only says, ‘Good fences make good neighbors.’

Some read that last line as a straightforward maxim, meaning: Boundaries keep things pleasant. But there’s a sadness to the poem. The puzzled narrator wants to know what, precisely, each man is walling in or out. To him, “Good fences make good neighbors” is ironic. It presumes people harm each other by getting too close.

In the Alabama pine forest that was once the Scotch Wildlife Management Area, there was once no need for walls. Gray Skipper’s family wanted the land to be enjoyed by the community. The family wasn’t required to open up their land to the public; they did it voluntarily, as stewards of a thriving habitat—as good neighbors.

And they were punished for it. The federal government gave the family a reason to put up walls.

A Family History

Gray learned the business from his uncle. (It’s his mother’s side of the family that owns the land and mill.) Gray was more interested in the lumber business than his brothers. “We were in several other lines of business,” Gray explains, “but I chose this one.” His great-grandfather W.D. Harrigan Sr. bought Scotch Lumber Company in 1902. (It was named after the Scottish ancestry of the previous owners.)

Harrigan set the tone for his descendants. It wasn’t just the lumber mill he cared about; it was the surrounding community. The company website describes Harrigan’s early efforts:

He built the first good road to Grove Hill, as it was the county seat, donated steel to construct a bridge over Bassett’s Creek, established station telephone service, and installed a water pump house and well, in addition to rental homes. He also constructed a commissary full of groceries and supplies, the county’s first four-hole golf course and swimming hole, and the first motion picture theater in Clarke County. Upon an annual return from the North, Mr. Harrigan brought the town’s first automobile back to Fulton.

Gray has been going to the land since he was a child. The wood they harvest goes into telephone poles, pilings, sawtimber, veneer logs, and other primary forest products. “We’ve been on this property for over a century,” he says,

and we have categorically improved the timber growing capability, the aesthetics, the wildlife, the accessibility through roads and different things. And it really hit us wrong when the federal government came in and placed those restrictions on us. It’s just a hard pill to swallow.

Victory in Court

In 2021, the Skipper family filed a lawsuit against the Fish & Wildlife Service. Pacific Legal Foundation represents the family free of charge, continuing our work to challenge abuses of the Endangered Species Act. Federal officials can’t lock down land on behalf of wildlife that may not even exist on the property. As we wrote in our complaint:

The Service made this designation despite the Skipper family’s objections, the best evidence suggesting that the black pine snake does not occupy their land, and the perverse incentives such designations create for landowners like the Skipper family who actively steward land to conserve forest habitat.

This August, the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Alabama issued its opinion: an emphatic victory for the Skipper family. The critical habitat designation was removed.

“[T]he record lacks concrete evidence that the black pine snake was present in [the area] at the time of the listing,” the court said. “An agency cannot use the presence of suitable habitat to expand the boundaries of the ‘occupied’ territory beyond where the species is actually found.”

The black pine snake is still listed as threatened—which is a shadow over the Skipper family’s land. Gray would like to see it delisted entirely, so he doesn’t have to dread a possible repeat of this nightmare.

This is what the Fish & Wildlife Service has done to landowners: They’ve turned the presence of rare animals into landmines no one wants. They’ve incentivized owners to shut down lands, put up walls, and stop letting the community in.

But PLF is fighting for landowners like the Skipper family—and with each victory, we roll back the shadow of federal overreach and return freedom to places like the Skippers’ pine forests.