Disqualified.

Four days after a 2024 horse race in New Mexico, Oscar Ceballos, the jockey who’d placed second, got bad news: He’d been disqualified, suspended, and fined $800. The horse he’d ridden, Alotaluck, would be recorded as “unplaced” in the race and disqualified from the $85,360 purse (the prize money).

Ceballos had apparently broken a rule from the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Authority (HISA), the private regulatory body Congress empowered in 2020 “to implement, for the first time, a national, uniform set of integrity and safety rules that are applied consistently to every Thoroughbred racing participant and racetrack facility,” according to HISA’s website. Headquartered in Kentucky, HISA has an $80 million budget (funded mostly by those it regulates), nine directors, and the power to create and enforce rules over racehorses, jockeys, trainers, owners, veterinarians, and racetracks.

One HISA rule: A jockey may only strike a horse with a crop six times during a race. Ceballos had hit his horse eleven times.

Ceballos appealed to HISA. His horse had been drifting out of his lane, or “lugging out,” he argued. He’d used the crop on the horse’s shoulder for safety, to control a dangerous situation.

HISA upheld the suspension and disqualification. Video of the race “clearly shows that the horse was lugging out and also moving toward the rail at different points,” the decision from HISA’s board acknowledged, confirming Ceballos’s account. But Ceballos was not “manifesting signs that he was concerned about safety” during the race, according to the board. The disqualification stood.

Ceballos appealed again, this time to the Federal Trade Commission, which oversees HISA. After an in-house hearing at the FTC, an administrative law judge overturned the decision and ruled for Ceballos.

The months-long dispute put a spotlight on the strange and controversial power of HISA—a young regulatory body wielding authority over America’s oldest sport.

A ‘Fascinating and Rational Amusement’

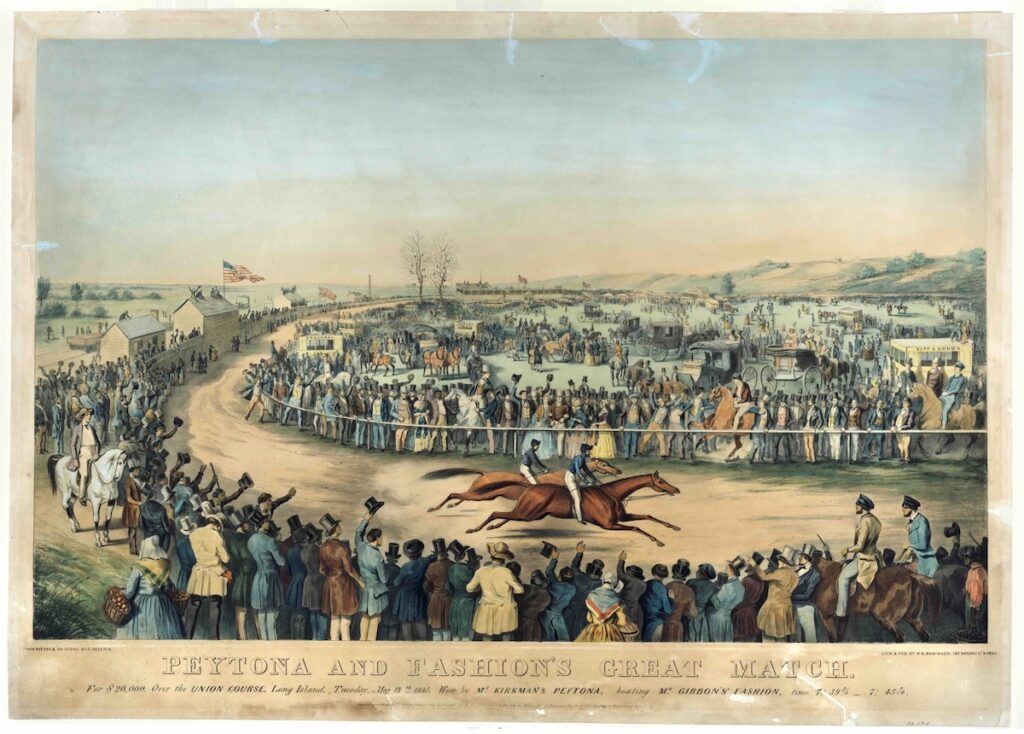

Before America had independence, we had horseracing.

Horses ran wild in the colonies—so wild that some colonies passed early laws to limit “the great Evils and Inconveniences” caused by horses running unbridled through town. By the mid-1600s, “horseracing had become a popular and largely unregulated recreation throughout the colonies,” Joan Howland writes in her legal history of Thoroughbred racing.

In England, racing was “the sport of kings”—the exclusive hobby of royalty and aristocrats—and at first, American courts mimicked English restrictions. A Virginia court fined a tailor a hundred pounds of tobacco in 1674 for betting on his horse to win a race: It was “contrary to Law for a Labourer to make a race, being a Sport only for Gentlemen,” the court proclaimed. But as Americans bristled against British rule, they began making their own horseracing traditions: Horsemen clubs formed and began enforcing rules for races so that British authorities wouldn’t interfere with the sport. By 1776, according to the book Blooded Horses of Colonial Days,

racing was established at almost every convenient town and public place in Maryland, in Virginia, and in the Carolinas, where the inhabitants, almost to a man, were devoted to this fascinating and rational amusement; when all ranks and denominations were fond of horses, especially those of the race breed…

For the next few centuries, horseracing was threaded into American history and culture. When Thomas Jefferson was president, he was such a renowned horseman that the Tunisian ambassador gifted him a stunning Arabian stallion that could sire racehorses. (Jefferson believed the Constitution prevented him from accepting, but he didn’t want to offend Tunisia. He arranged for the government to accept the horse and later auction it.) When prospectors moved west for the Gold Rush, they made California “a Mecca for Thoroughbred racing,” according to Howland. In the 1930s, the racehorse Seabiscuit was featured on Manhattan billboards. When Secretariat won the Kentucky Derby in 1973, the crowd watching was twice the size of the 2025 Super Bowl attendance.

During all this time, up until the year 2020, horseracing was regulated through a distinctly American mix of state racing commissions, localities, and civil society. But that changed when Congress passed the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Act, giving power to a new authority.

Bill’s Story

“We never had an opportunity to voice our objections to it,” says Bill Walmsley, the 83-year-old president of the Arkansas Horsemen’s Benevolent and Protective Association.

Congress passed the Horseracing Integrity and Safety Act three days before Christmas in 2020 as part of the omnibus year-end spending bill—a legislative tactic that barely gives congressmen time to read a bill, let alone debate it. The bill recognized a new “private, independent, self-regulatory, nonprofit corporation, to be known as the ‘Horseracing Integrity and Safety Authority.’” HISA is now a private corporation that exercises the power of the government: It writes and enforces horseracing rules that the FTC is legally obligated to approve as long as they’re “consistent” with the statute.

Bill is one of many horsemen suing the government for unconstitutionally delegating power to HISA.

“I believe it’s the most undemocratic regulatory scheme that I have ever seen,” Bill Walmsley says.

He knows what he’s talking about: Bill is a retired judge and former Arkansas state senator who’s been involved in horseracing for decades. He was elected to the Arkansas State Senate at the age of 28, after putting himself through college on a basketball scholarship and borrowing money to go to law school.

“Like many young people, I was probably more fearless than cautious,” he says. That made him popular with the Arkansas press. It also led to him befriending several older, wealthier gentlemen—one of whom got Bill into horseracing.

Bill already loved the races at Oaklawn, a racetrack built in 1904 in Hot Springs, Arkansas. After he left the state senate, Bill was approached by a wealthy mentor who wanted to get involved in horseracing, “but he didn’t want to do the details and the necessary work,” Bill says. “He just wanted to be able to go and watch his horses run.” The men became partners in a Thoroughbred racehorse, with Bill’s mentor carrying most of the financial burden and Bill handling the work.

“That got me started,” Bill says. He and his longtime business partner now try to have at least three horses in training always. Their horses start around 20 races a year and can win hundreds of thousands of dollars in purses.

Then there’s the Horsemen’s Benevolent and Protective Association: Bill was president of the national organization—which represents 30,000 owners and trainers—from 1992 to ’96. Now he’s president of the Arkansas chapter, which takes a percentage of the purses at Oaklawn and uses them to help people who work in the stables. The association built a health clinic at Oaklawn where grooms and other workers receive free medical care; it hosts holiday dinners for the workers and buys Christmas gifts for their children; and it has a chapel where workers can learn English as a second language or attend alcohol abuse recovery programs.

“We also have a program for the racehorses,” Bill explains. The association runs a farm where retired racehorses can be cared for by a former jockey until an adoption is arranged.

This is all good, meaningful work—the kind of thing Alexis de Tocqueville was referring to when he said, “Everywhere that, at the head of a new undertaking, you see the government in France and a great lord in England, count on it that you will perceive an association in the United States.”

Since HISA was created, however, part of the association’s time is spent helping trainers fill out required HISA forms. Trainers are exceptional with animals, Bill says. That doesn’t make them good at filling out government paperwork. “And a lot of them have really struggled with the bureaucratic filings they have to make with HISA,” Bill says. “There’s a huge amount of filings.”

All owners, trainers, and jockeys are required to register with HISA and pay fees. Trainers must provide meticulous records on horses. HISA decides how much medication horses can take, what they can eat, how long and wide a riding crop may be, and how often a jockey can use that crop. HISA’s own rules give it access to the books, records, offices, racetrack facilities, and businesses of people in horseracing—and sanctions for rule violations can top $100,000.

In fact, Bill says, HISA’s regulations “deal with every single aspect of the Thoroughbred industry,” Bill says. “And in the greatest and in the most minute details.”

The Lawsuit

Bill is one of many horsemen suing the government for unconstitutionally delegating power to HISA. He and Jon Moss, president of the Iowa chapter of the Horsemen’s Benevolent and Protective Association, are represented by Pacific Legal Foundation. “A private, unelected, and unaccountable body controls a legendary and iconic American industry,” PLF wrote in the initial complaint. “Our Constitution does not permit unaccountable private actors to wield such power.”

The Supreme Court is now considering taking Bill and Jon’s case. It’s one of several petitions challenging HISA that are currently before the Court, and with circuit courts split on the issue—with the Eighth and Sixth Circuits ruling for HISA but the Fifth Circuit calling it unconstitutional—the Supreme Court is likely to hear a HISA case. (The Court has conferenced on PLF’s petition, but as of this writing it’s still pending.)

Meanwhile, the 2025 horseracing season is well underway at Oaklawn and other racetracks across the country, and HISA’s power remains in full effect.

To Bill Walmsley, HISA “just violates the principles on which our country stands. And that’s what bothers me so much about it.”

Thoroughbred racing is part of America’s sporting heritage, he says. “It’s always been run by state racing commissions.” Even if you think a national system could do a better job, the state commissions “ought to at least be involved,” Bill says. “In this case, they were not involved at all with the creation of HISA. They were totally ignored.”

Underlying his frustration is his genuine love for horseracing: You can hear it in his voice. The people opposing HISA aren’t doing it out of bitterness or a kneejerk reaction to federal rulemaking; they’re doing it because HISA is interfering with this sport that has meaning in their lives.

“I have won 140 Thoroughbred races,” Bill says. “And I never cease to get terribly excited when a horse goes to race.” It doesn’t make a difference whether the purse is big or small, he says. “It just doesn’t. It’s a terribly exciting thing to me.” Thoroughbred horses are phenomenal athletes to watch run. “And I just love it,” Bill says. “I love the sport.”