Willie Mays was out at home plate.

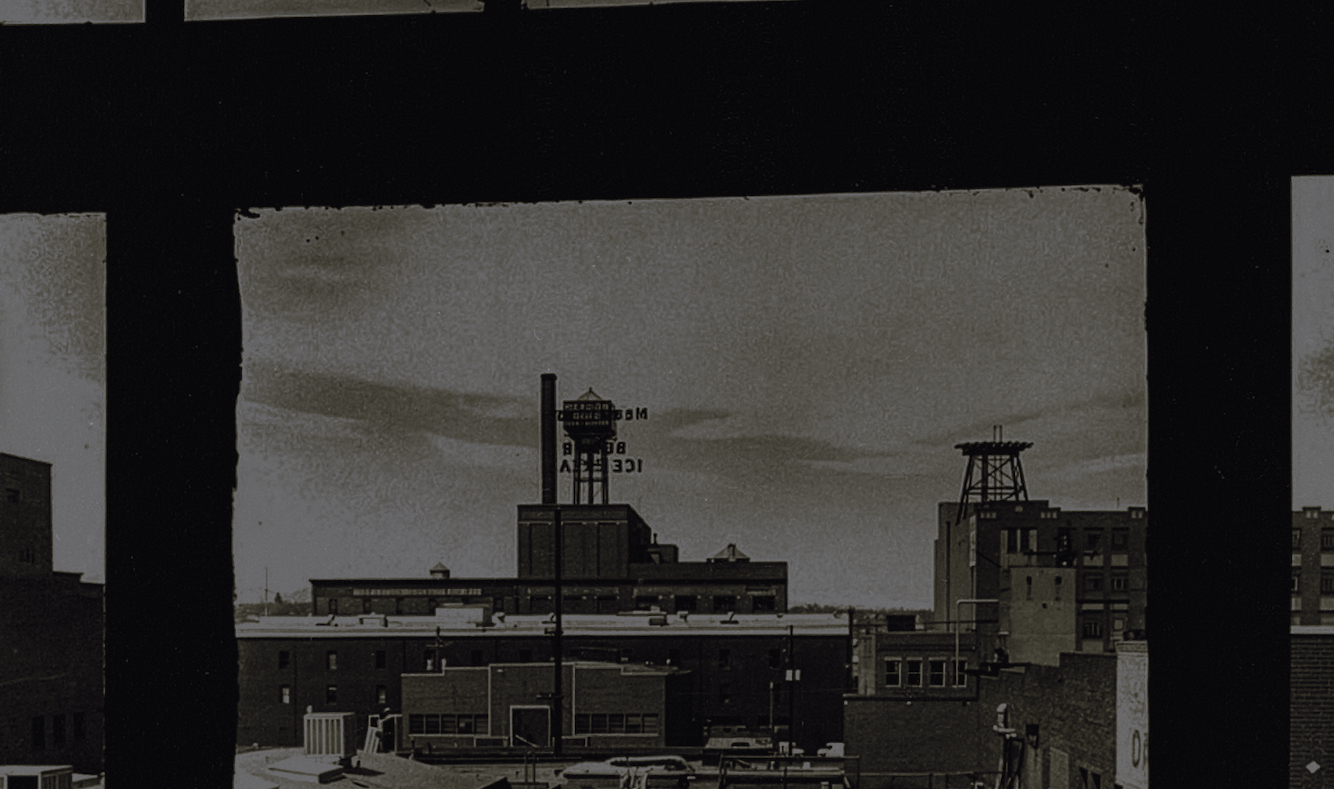

It was August 10, 1955, and the New York Giants were playing a night game against the Brooklyn Dodgers at Ebbets Field, the Dodgers’ worn-down stadium in Flatbush. The bases were loaded at the top of the fifth with Mays, the Giants’ star centerfielder, on first. The Giants trailed 5-2.

The batter hit a double, setting the field in frantic motion: One Giants runner sprinted home, then another. Mays—the fastest man in baseball—was legging it from first, trying to tie the game 5-5. Dodgers infielder Don Zimmer threw the ball home for a close play at the plate: Out.

O’Malley announced he was packing up the Dodgers and moving them cross-country to Los Angeles, where city officials had already used eminent domain to take over a large plot of land…

Mays thought he was safe: He and the Giants manager argued with the home plate umpire while the crowd at Ebbets watched. It began to rain. The teams played only one more inning before the game was called: The Brooklyn Dodgers had beaten the World-Series-Champion Giants.

It was perfect timing for Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley, a New York businessman and corporate attorney. Earlier that day, O’Malley had written to the City of New York: He wanted a new stadium for the Dodgers, who were having their best-yet season. Ebbets, built in 1913, was too old and cramped for O’Malley’s big-time ambitions. There were hardly any parking spaces and no feasible way to expand into the surrounding neighborhood.

O’Malley had money. And he had the perfect spot picked out for a new Dodgers stadium: the corner of Atlantic and Flatbush avenues. What he needed was government power. He knew that if he tried to buy up parcels of land individually, some property owners would hold out or hike their prices. So O’Malley asked New York City to seize the land using Title I of the Housing Act of 1949, which encouraged (and directed federal funds toward) cities clearing slums through eminent domain.

A few days later, Robert Moses—the famed urban planner and commissioner of the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation—wrote back.

“I can only repeat what we have told you verbally and in writing,” Moses told O’Malley, “namely, that a new ball field for the Dodgers cannot be dressed up as a Title I project.”

A Public Use

Sports stadiums are strange beasts: They take up huge tracts of land, can transform neighborhoods—although, research shows, not necessarily to the financial benefit of local businesses—and yet they mostly benefit the private owners of the sports teams that play there.

Because of the size and nature of the project, the government is inextricably tied up in the construction of a new stadium. But to what extent can the government use its coercive powers to get sports stadiums funded and built?

That depends on how you interpret “public use.” The Constitution limits the government’s power to take private property in two fundamental ways: The taking must be for a public use and the owner must be justly compensated. A sports stadium—where privately owned teams play in front of spectators who pay to watch while broadcasters pay to broadcast the game—isn’t exactly a public park anyone can use. Robert Moses tried to tell Walter O’Malley that seventy years ago.

The Dodgers Say Goodbye

The Dodgers won their first World Series in 1955, a few months after Robert Moses turned down Walter O’Malley’s pitch. The two men argued back and forth over the next two baseball seasons, with O’Malley insisting New York needed to exercise its power to take private property for a public purpose—because wouldn’t the public love a new Dodgers field with more parking?

Moses said New York couldn’t condemn and seize private land to make it easier for O’Malley to build. But he suggested an alternative: New York could build a publicly financed and publicly owned stadium, instead. Would O’Malley be interested in the Dodgers playing in a public stadium?

He would not.

On October 8, 1957, O’Malley announced he was packing up the Brooklyn Dodgers and moving them cross-country to Los Angeles, where city officials had already used eminent domain to take over a large plot of land in Chavez Ravine, displacing the Mexican American families who lived there. The area was originally intended to become public housing, but that project had fizzled. Los Angeles would give it to the Dodgers for a stadium instead.

Back in New York, Robert Moses was unrepentant. Walter O’Malley was demanding “a strictly Dodger stadium, custom-made to his own measurements and specifications, and with little or no regard for broader recreational use,” Moses explained in a column. “From the point of view of constitutionality, Walter honestly believes that he in himself constitutes a public purpose.”

A Common Practice

Decades later, cities and states across the country—including New York—have supported new sports stadiums not only through subsidies (paid for with tax hikes) but also by seizing private property through eminent domain.

Reason magazine writes:

Sports owners have long used eminent domain as a way to acquire property cheaply. Sports economists estimate that half of the post-1990 stadium and arena construction has involved eminent domain—and even when it wasn’t invoked, it was understood that condemnation could be a last resort if the teams encountered stubborn landowners.

Take Arlington, Texas. In the 1990s, the City used eminent domain to take property from hundreds of private owners to make way for a new Texas Rangers stadium. When the Dallas Cowboys wanted a new stadium in the mid-aughts, Arlington again exercised its takings power. This time, property owners sued Arlington, arguing the Cowboys stadium wasn’t a valid justification for a government taking and that the City had lowballed their compensation. A special commissioner was brought in to increase the compensation packages. But as for the validity of the project, the Court of Appeals of Texas held that

the mere fact that a private actor will benefit from a taking of property for public use . . . does not transform the purpose of the taking of the property, or the means used to implement that purpose, from a public to a private use.

The Arlington decision came in 2009—four years after the Supreme Court ruled against Connecticut homeowner Susette Kelo in a takings case that broadened the definition of public use to, essentially, anything that might boost a city’s economy. In Kelo, at least, the Supreme Court made clear that the government isn’t allowed to “take property under the mere pretext of public purpose, when its actual purpose [is] to bestow a private benefit.”

Yet that’s exactly what New Yorkers say happened with the Brooklyn Nets’ new arena less than a decade later—mere feet from the tract of land Walter O’Malley originally sought for the Dodgers, at the corner of Atlantic and Flatbush.

Playing the Eminent Domain Game

New York real estate developer Bruce Ratner knew he wanted to own the land at Atlantic and Flatbush before he even owned the Brooklyn Nets basketball team.

The site was a diamond: Twenty-two acres of underdeveloped property only 20 minutes from Manhattan, where the Long Island commuter rail and 11 subway lines all converged. Ratner had a vision: He could turn it into a billion-dollar mix of commercial, residential, and recreational properties. The only problem was that the property wasn’t vacant—14 of the acres were occupied by warehouses and homes.

Malcom Gladwell recounts the story in Grantland:

To buy out each of those landlords and evict every one of their tenants would take years and millions of dollars, if it were possible at all. Ratner needed New York State to use its powers of “eminent domain” to condemn the existing buildings for him…

Ratner knew this would not be easy. The 14 acres he wanted to raze was a perfectly functional neighborhood, inhabited by taxpaying businesses and homeowners. He needed a political halo, and Ratner’s genius was in understanding how beautifully the Nets could serve that purpose.

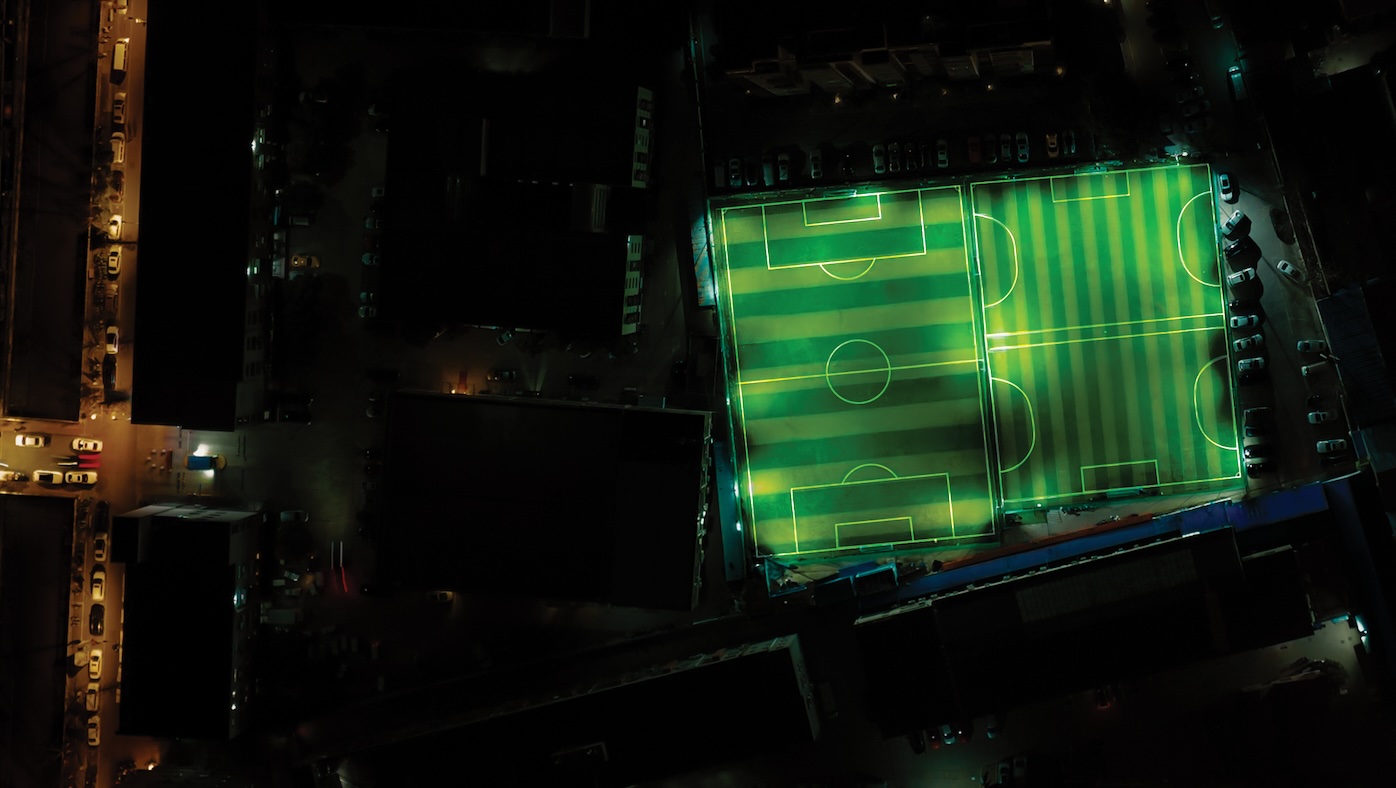

Ratner bought the New Jersey Nets in 2004 with the express purpose of moving their arena to his selected intersection in Brooklyn, with the government’s help. He wasn’t just buying a basketball team; he was buying “eminent domain insurance,” as Gladwell put it. The arena would be the justification for—and centerpiece of—Ratner’s billion-dollar development. When The New York Times reported on the Nets’ new ownership, it included Ratner’s plan to have New York condemn property so he could move the team to Flatbush and Atlantic, “where Walter O’Malley was rebuffed nearly half a century ago in his efforts to build a new stadium for the Brooklyn Dodgers.” This time New York leaders were on board. Property owners sued, and the process dragged on for years, but the government managed to clear the land Ratner coveted. In 2012, the newly renamed Brooklyn Nets began playing at their sparkling new arena, Barclays Center.

Who Loses

Justice Sandra Day O’Connor dissented from the majority opinion in the Kelo case. “Under the banner of economic development,” she warned, “all private property is now vulnerable to being taken and transferred to another private owner, so long as it might be upgraded…”

That’s precisely what happens when the government takes private property for sports stadiums. And economists have shown there’s not even a guaranteed boost to local businesses from stadiums.

Meanwhile, displaced families and businesses bear the cost. Some end up with windfalls: One property owner who fought the Nets’ taking in court eventually backed down when Ratner, desperate to end litigation, offered $3 million for the owner’s home, which the City had appraised at $510,000.

But other property owners simply lose. After Walter O’Malley moved the Dodgers to Los Angeles in 1957, his team played in a temporary facility for several years while the City cleared the last resisting property owners out of Chavez Ravine. They were never fully compensated: A judge lowered the offering price to $10,050.

In 1959, Los Angeles deputies dragged one of the last Chavez Ravine holdouts, a thirty-seven-year-old World War II widow named Aurora Vargas, from her home. Afterward her father said, “My family and I fought every way we knew how to stay in our home in Chavez Ravine. … We lost our home and our land, but we didn’t lose our pride because we fought with everything we had.”