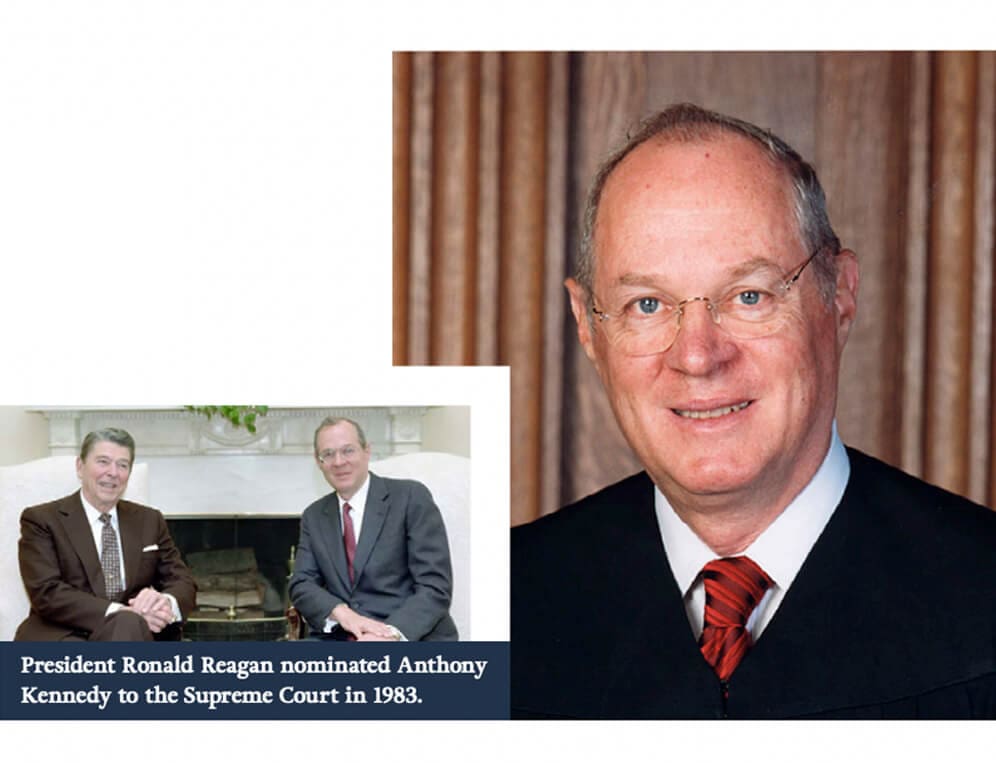

AT THE END of the last term, Justice Anthony Kennedy announced his retirement from the U.S. Supreme Court. Although his considerable power as the Court’s “swing justice” occasionally made him a controversial figure, Kennedy’s place in the Court’s history should be defined by his deep appreciation for the role of free speech in our Constitution and society. Hopefully our next Justice will continue his commitment to a strong First Amendment.

Perhaps more than any of his colleagues, Kennedy recognized the human impact of the Court’s work. He believed that, even if a majority of Americans may disapprove of elements of a person’s private life, all people “retain their dignity as free persons”—and the Court must come to their aid when their liberty is threatened.

“Speech,” he explained, “is an essential mechanism of democracy, for it is the means to hold officials accountable to the people.”

—Justice Anthony Kennedy

Kennedy also appreciated the Constitution’s promise of ever-expanding liber ty, noting that “as the Constitution endures, persons in every generation can invoke its principles in their own search for greater freedom.” In that vein, Kennedy will be remembered by many as the justice who most expanded equal protections to gays and lesbians.

Kennedy authored the Supreme Court’s Citizens United v. FEC decision, perhaps the Court’s most important political speech case in the past decade. Writing the majority opinion, he rejected the federal government’s claim that it could ban movies and books critical of politicians and candidates. “Speech,” he explained, “is an essential mechanism of democracy, for it is the means to hold officials accountable to the people.” Consequently, allowing politicians to censor their critics would pose a significant threat to our democracy.

Justice Kennedy also wrote the opinion in Packingham v. North Carolina, striking down the state’s overly broad ban on social media use by registered sex offenders. Acknowledging the importance of the state’s interests in protecting children, he concluded that a state could not bar “access to what for many are the principal sources for knowing current events, checking ads for employment, speaking and listening in the modern public square, and otherwise exploring the vast realms of human thought and knowledge.” In other words, the state may police and punish crimes, but it can’t use that as an excuse to ban people from the internet.

Kennedy’s commitment to First Amendment values carried through to his final term. He voted with the majority of his colleagues in Minnesota Voters Alliance v. Mansky. That case, PLF’s 10th Supreme Court victory, struck down Minnesota’s vague ban on political apparel at the polling place, which invited arbitrary enforcement.

In one of his final opinions, Kennedy concurred with the Court’s decision to strike down a California law compelling pro-lifers to spread the state’s pro-choice message. He wrote separately to admonish the state that it isn’t progressive to force people to say what they don’t believe. Instead, “it is forward thinking” to appreciate the First Amendment’s lessons “and to carry those lessons onward as we seek to preserve and teach the necessity of freedom of speech for the generations to come.”

We can only hope Kennedy’s successors will share his commitment to these principles.