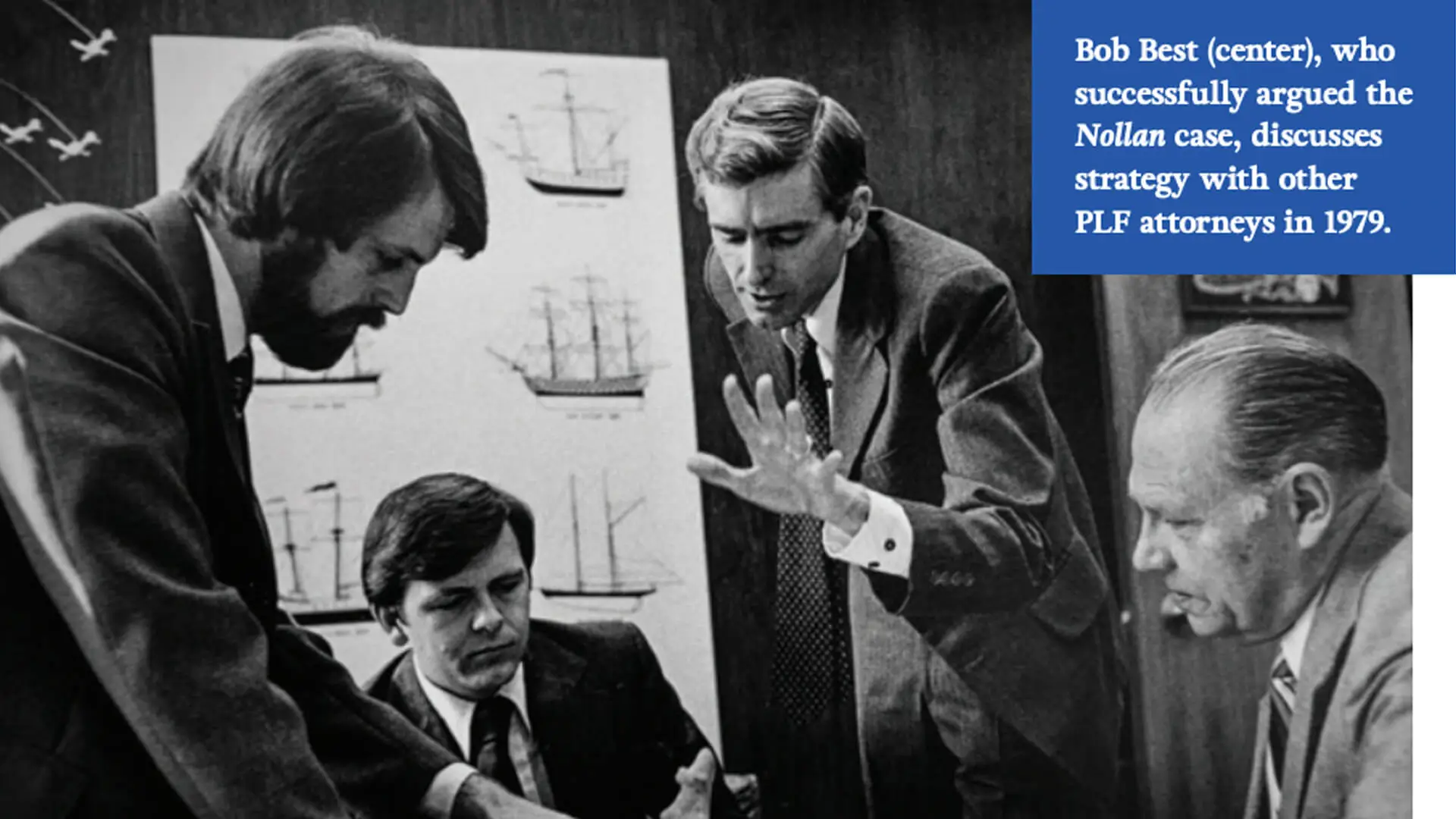

GOVERNMENT CANNOT STEAL. That was the essence of Justice Scalia’s majority opinion in Nollan v. California Coastal Commission. If government demands someone’s property in exchange for a permit, then the taking of the property must reduce a serious harm caused by the permitted development. It’s not enough that the government might want the property for “the public good.” Instead, the taking must directly reverse a harm that would otherwise be caused by the development.

But even this modest limitation on government power has been fought tooth and nail by avaricious government agencies that believe that there is such a thing as a free lunch—for them. A free lunch, a free hiking or bicycle path, or a free check with lots of zeros; whatever government wants it will try to take.

In the 30 years since Nollan, we have been fighting back to defend the bedrock constitutional principle that government cannot take private property unless it is willing to pay for it. For every holding we’ve won at the U.S. Supreme Court, government lawyers have dreamed up new loopholes. For every loophole, we’ve marshalled our forces with the goal of getting back to the Supreme Court. Fortunately, in this game of whack-a-mole with government, we’re winning. But we’d be naive to think we’ve won.

But government was undeterred. After losing in land and bike-path grabs, governments started to demand money, saying that cases like Nollan were about demands of real estate and that a demand for money was somehow different. But isn’t money property? After many years fighting governments across the nation on their money-doesn’t-count theory, we finally went back to the Supreme Court in Koontz v. St. Johns River Water Management District. There, the district demanded more than $150,000 in improvements on government land in exchange for a building permit. It said Nollan didn’t apply because it was only asking for money. The Supreme Court didn’t buy it and called the scheme an unconstitutional extortion.

After we won Nollan, some local governments began to get creative. The City of Tigard, Oregon, told a store owner that she had to build a bike path if she wanted to add store space and extra parking. After all, the City claimed, the parking spaces might add traffic that could be eased by the bike path. Thus in Dolan v. City of Tigard, a case where we were a friend of the court, the Court ruled the demand for property had to be “roughly proportional” to the impact. Clearly, a new bike path wasn’t proportional to a few parking spaces.

But government was undeterred. After losing in land and bike-path grabs, governments started to demand money, saying that cases like Nollan were about demands of real estate and that a demand for money was somehow different. But isn’t money property? After many years fighting governments across the nation on their money-doesn’t-count theory, we finally went back to the Supreme Court in Koontz v. St. Johns River Water Management District. There, the district demanded more than $150,000 in improvements on government land in exchange for a building permit. It said Nollan didn’t apply because it was only asking for money. The Supreme Court didn’t buy it and called the scheme an unconstitutional extortion.

Lately, government agencies have taken to arguing that if an exaction for land or money is established not by a permitting agency but by a legislative body, like a city council, then Nollan doesn’t apply. We’re seeing that gambit now when cities demand that home builders set aside homes for below-cost sale to low-income residents or pay a fat check in lieu of the set-aside. Since these schemes are ginned up by city councils, rather than a planning department, the cities claim immunity from Nollan. We’re working very hard to ride this horse for our next trip to the Supreme Court.

The lesson here is that when it comes to beating back government on constitutional violations, our work will never be done. For every victory we achieve, governments will try evasion, obfuscation, and massive resistance. Eternal vigilance, backed by eternal litigation, is the price of liberty. That’s why PLF goes to court.