DAVE BREEMER IS a senior attorney at Pacific Legal Foundation who surfs in his free time and greets you with a cheerful “what’s up dude.” He’s also a biting pragmatist and one of the most successful attorneys in PLF’s history. He describes himself as “a Christian first. After that, none of the other stuff really matters that much.” He is at the same time remarkably humble and overwhelmingly self-assured. When summing up his approach to his life and career, he explains, “If you’re dedicated to a higher purpose, you don’t really let nine Justices in DC worry you.”

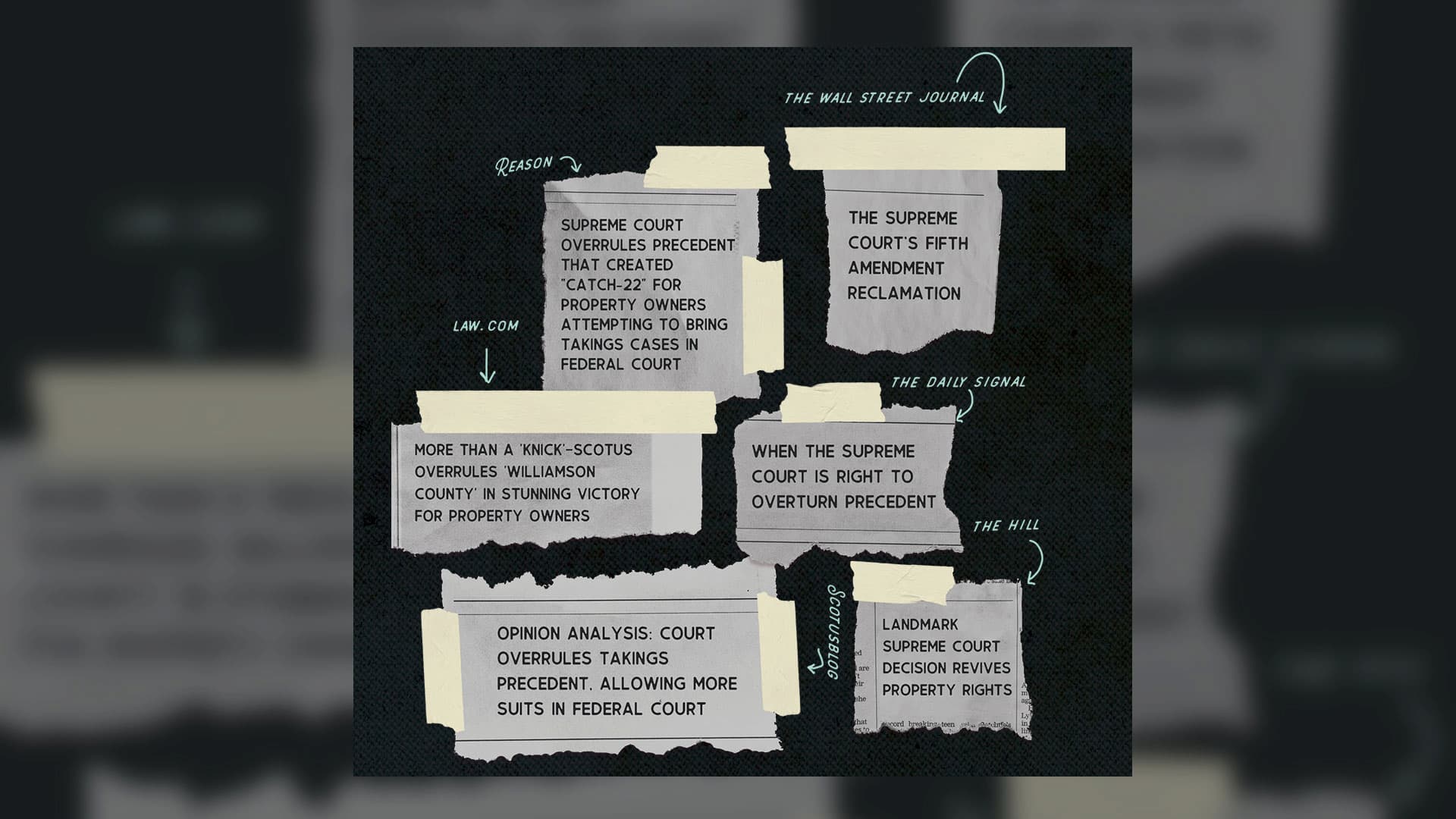

Dave was thoroughly uninterested in talking about himself during our phone interviews in the weeks following his Supreme Court victory in Knick v. Township of Scott, a case that overturned a legal precedent known as Williamson County, and a victory he’d been working toward nearly 20 years. “I hate this stuff, I’m not good at talking about myself” was the most common answer to any question about his personal journey to overturning one of the most hostile property rights precedents in decades.

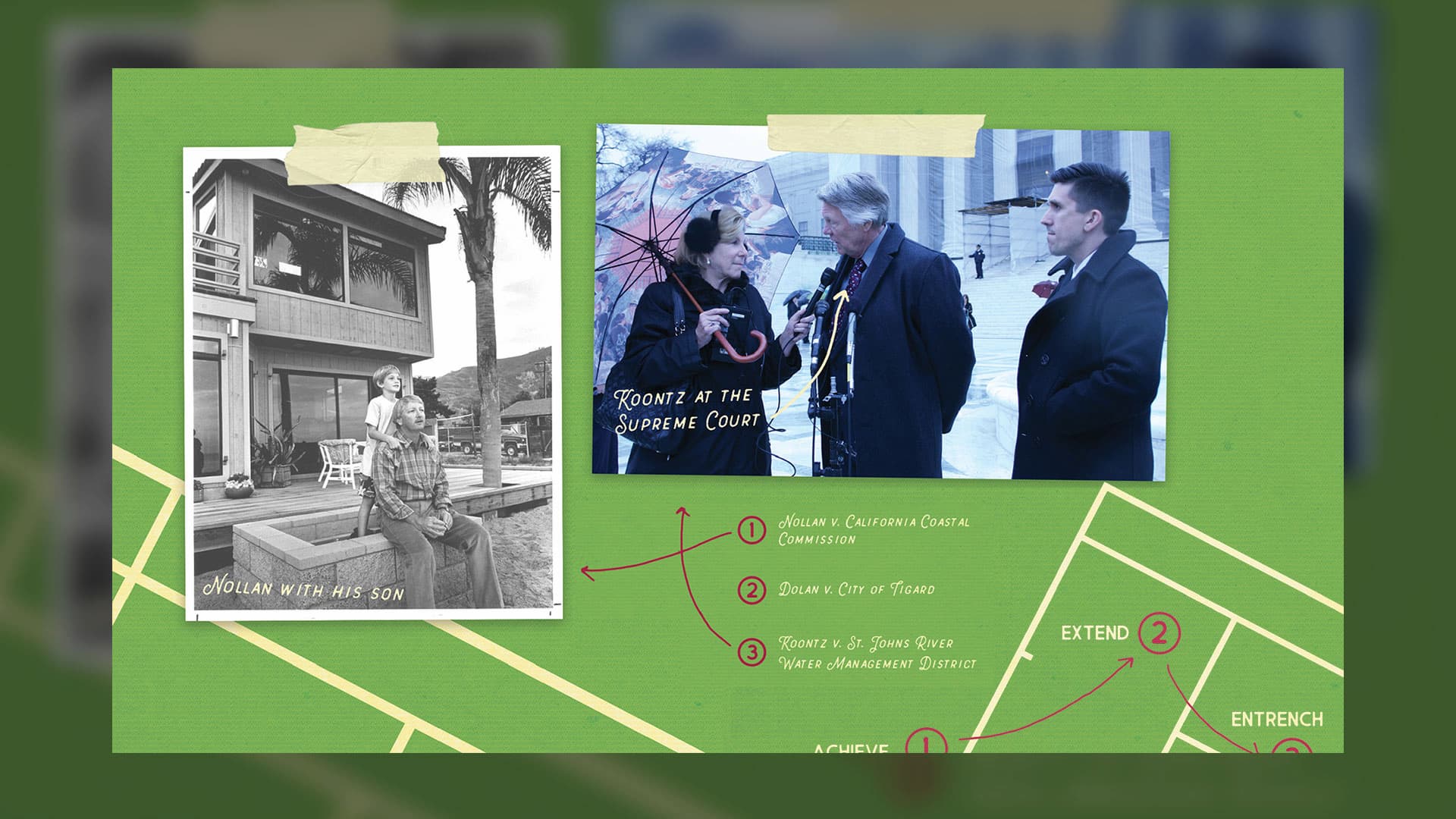

Among other cases like Penn Central v. New York City and Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Williamson County has been on PLF’s most-hated precedents list for a long time. Williamson County v. Hamilton Bank was a 1985 Supreme Court decision that created a near- insurmountable hurdle for property owners trying to stop the government from taking their property without paying for it. Hamilton Bank in Tennessee was trying to develop a residential subdivision but was denied building permits because the local planning commission claimed the subdivision violated zoning regulations. Hamilton Bank sued, claiming that Williamson County violated their property rights by reducing the value of their land.

The case eventually made it to the Supreme Court, where the Court ruled against Hamilton Bank and said that cases like theirs had to work their way through state courts before they could be argued in federal court. While federal courts were available to those facing other injustices, such as censorship and discrimination, the Williamson County decision demoted countless property owners to second-class citizens in the law.

Dave started at PLF in 2001. George W. Bush was the country’s newly sworn-in president, consumers were marveling at the first iPod, and New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani was named Time magazine’s Man of the Year for his leadership in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of September 11. And at that time, despite it being unknown outside of legal circles, Williamson County was locking thousands of property owners out of federal court.

If you ask Dave why he chose this target, he answers as a freedom-loving idealist: “I saw that [Williamson County] was being used as a tool to prevent people from defending their constitutional rights—I saw it was hurting people.”

Dave had his bull’s eye. But now he needed cases.

Hitting the brick wall

The Williamson County precedent was set by the Supreme Court, so it would require a Supreme Court victory to overturn it. How easy would that be? On average, more than 6,000 cases are submitted to the Court each year, but only 70 to 80 are actually heard. But despite the odds, Breemer admits that as a younger attorney, he thought victory against Williamson County would come relatively quickly. After all, he reasoned, it was an absurd legal doctrine, was widely accepted as harmful (as long as you weren’t a lawyer for the government), and there were myriad cases that could strike it down.

The 2005 case SFW Arecibo v. Rodriguez seemed like a perfectly fine opportunity to overturn Williamson County. Two real estate developers in Puerto Rico were denied a permit for their development project, so they sued the local government and had their case thrown out of court because of the Williamson County precedent. But the Supreme Court denied Dave’s request to have it hear the case, known as a petition for writ of certiorari.

Ok, it’s just one setback.

In 2007, with Braun v. Ann Arbor Charter Township, Dave had another shot. Two farming families tried selling their land to developers who wanted to build homes on the properties. But the local government denied their rezoning application, so the families sued the township. Just like SFW Arecibo, the case got thrown out because of Williamson County. Dave wrote another petition for a writ of certiorari for the Supreme Court—and got another rejection.

For the next three years, Dave relived the same judicial outcome for every property rights takings case he argued across the country: Peters v. Village of Clifton in 2007, Snaza v. City of Saint Paul in 2008, and Salt Pond Partners v. State of Rhode Island in 2010.

In each case, Dave explained the legal merits against Williamson County and showed how it was throwing plaintiffs into legal and financial ruin. He wrote law review articles on Williamson County—five over the course of 14 years—and gave talks at seminars and law schools. Yet, Williamson County remained alive and well, and the Supreme Court closed the door on every one of Dave’s attempts to end the Williamson County precedent.

It’s hard to know why the Court refused to hear arguments on Williamson County for so long. But perhaps the reason was a point the government’s lawyer would later make during the oral arguments for Knick: The law had been on the books for years and the country’s legal and government bodies were used to it. Dave and PLF saw the harm Williamson County was causing families, businesses, and property owners across the country. But from a government official’s cynical perspective, the world wasn’t coming to an end simply because Williamson County was on the books.

Dave never considered giving up, that’s not really in his DNA.

When describing his motivations, he boils it down to: “I don’t want to do a bunch of work for nothing. I don’t want to do something just for a pay check. I want it to mean something. Winning drives me.”

But Dave wasn’t winning the Williamson County war. And at the rate the cases were going, winning wasn’t on the horizon any time soon.

It was time for a new strategy.

The first cracks

Starting in 2008, Dave decided that if he would ever have any hope of overturning Williamson County, it would have to be death by a thousand cuts. Williamson County prevented plaintiffs with property rights takings cases from suing the government in federal court. But what about very specific or unique takings cases? Were there exceptions to the rule? Dave sought to create and exploit holes in Williamson County and pursued cases uniquely positioned to show its flaws.

Dave’s next two cases, Severance V. Patterson in 2009 and Acorn Land, LLC v. Baltimore County in 2010, were the first cases that proved those holes existed. Severance was a Texas case that dealt with public beach access on private property, and Acorn Land, LLC was a Maryland zoning case. They were mixed decisions, with the courts agreeing with Dave and the plaintiffs on some parts, and the defendants on others. But for both, the courts were forced to admit that in some property rights takings cases, Williamson County shouldn’t apply. There are some specific instances where property rights takings cases can be heard in federal court.

In other words, a non-lawyer definition of Dave’s strategy was: If you can’t get anyone to admit the emperor has no clothes, try getting them to at least point out he’s not wearing a belt.

PLF Senior Attorney Deborah J. La Fetra explained why Dave’s revised strategy started bearing fruit. “There are really two ways to get to the Supreme Court: litigation or writing. Few attorneys do both as well as Dave has. His writings reach judges, and also help teach new attorneys learning about Williamson County and takings cases. So he’s influencing people deciding the law today, but also influencing people who will litigate the cases. Then, to approach litigation like he did by not simply trying to continually take Williamson County head on, but to attack it from the sides and the top and bottom. That’s what was remarkable about it.”

The crumbling of Williamson County

In Town of Nags Head v. Toloczko in 2013, the Toloczko family sued their North Carolina beach town after the Town attempted to force them to demolish their own beach cottages and allow the public to use their private land. The Town tried using Williamson County to get the case thrown out, but due to the specifics of the case—and the absurdity of the Town’s actions—the court agreed with the Toloczkos and allowed the case to go forward. Facing a possible defeat, Nags Head settled with the Toloczkos and paid them $200,000 in damages.

It’s impossible to know if a case like Toloczko would turn out the same way if it had been argued 10 years earlier. When talking to younger attorneys, Dave tells them, “Each case is its own animal with its own issues and its own possibilities. You have to look at it that way.”

Seeing more chinks in Williamson County’s armor, Dave brought six cases in six years that argued different aspects of Williamson County and won new precedents in each.

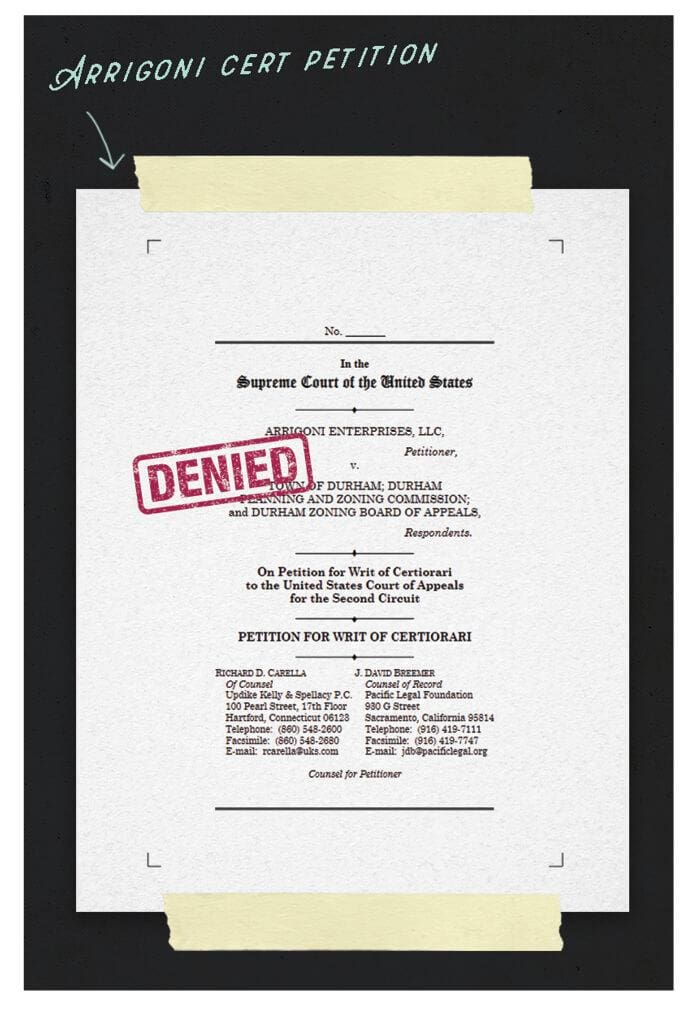

Then in 2015, Arrigoni Enterprises V. Town of Durham represented a potential turning point. Arrigoni was another property rights case where a property owner was forced to sue after the government denied their building permits. The plaintiff was caught in the Williamson County purgatory between state and federal court, unable to get any court to hear their takings complaint. So Dave and PLF tried to take the case to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court denied Dave’s petition in Arrigoni, but there was an important caveat. Justices Clarence Thomas and Anthony Kennedy dissented to the Court’s denial (meaning they thought the Court should take the case) and quoted one of Dave’s law review articles in their dissent.

Justice Thomas’ dissent was clear in its message: “In the 30 years since the Court decided Williamson County, individual Justices have expressed grave doubts about the validity of that decision and have called for reconsideration. This case presents the opportunity to consider whether there are any justifications for the ahistorical, atextual, and anomalous state-litigation rule, and if not, to overrule Williamson County. I respectfully dissent from the denial of certiorari.”

Was this the battle call that Dave had been searching for? “No!” he exclaimed when asked. “I was really disappointed. Maybe at one point in my career I would have been excited about two Justices agreeing with me, but at that point, I just wanted them to grant the case.”

Despite Dave’s disappointment with the Court’s denial in Arrigoni, their dissent was an important signal: There were at least two Justices who wanted attorneys to keep trying. And Dave and his new client, a grand-mother from Pennsylvania named Rose, were ready to answer the call.

Dave and Rose go to Washington

In 2013, Rose Knick sued her local government over a cemetery law that forced her to open part of her private farm to the public so people could visit gravestones that were never proven to exist. In many ways, Knick was the perfect case to overturn Williamson County. The plaintiff, Rose, just wanted to be compensated for the land that the government had taken from her. But Williamson County threatened her right to have her case fairly heard in court. Rose’s case followed the same narrative as Dave’s other Williamson County cases. It was thrown out of court after court, and then Dave submitted his petition to the Supreme Court. Some PLF attorneys speculated that Knick would be granted because Rose’s situation was so clearly a taking. That would allow the Justices to focus squarely on the issue of Williamson County. But the Court doesn’t comment on why it takes some cases and not others—it’s a blind shoot from our perspective. All Dave could do was wait.

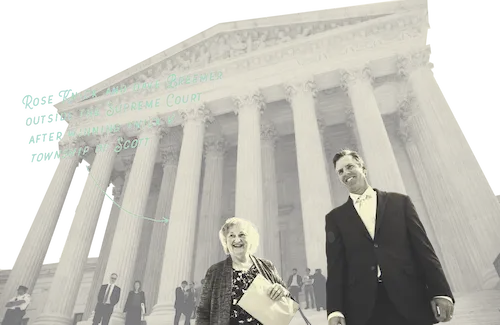

Finally, on March 5, 2018, the Supreme Court agreed to hear Rose Knick’s case.

PLF’s all-staff email exploded into a flurry of activity and congratulations. Dave never drinks champagne, but for that one evening, PLF staff in states across the country made sure bubbly flowed from sea to shining sea.

Everything surrounding the Supreme Court is in a heightened state. The pomp and ceremony are unavoidable. And on top of that, attorneys must face the knowledge that any screw-up will not only affect their clients, it will affect the legal future of our nation.

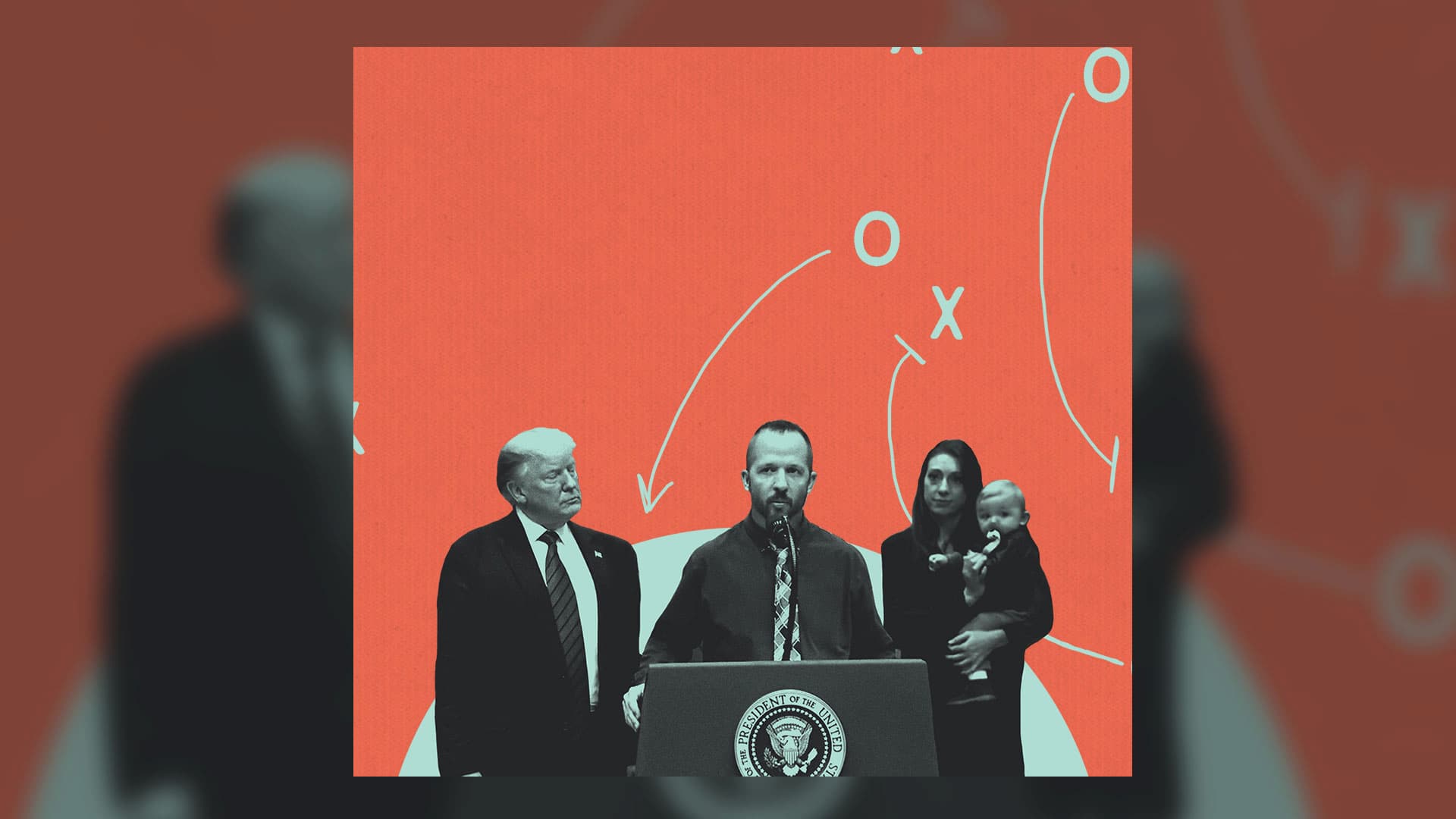

Dave describes the Court as “an extremely pressure-packed situation. It’s like playing in your first Super Bowl when you’ve been trying to get there for 15 years.” But on both oral argument days for Knick (the Court heard Knick twice), Dave was oddly calm. His steady nerves walking into the courthouse were a product of 20 years of preparation and the feeling that all his work had led him to this moment.

“I felt in my heart, or my spirit—whatever you want to call it—that it was the right time,” he says, looking back. “I’d sent up a lot of prayers about getting Williamson County to the Court, and I’d spent a lot of time learning how to get it right when the time did come. So…I kind of just had a good feeling about this case.”

Supreme Court oral arguments are a strange mix of ceremony, respectful discourse, and caustic debates. The Justices look for holes in each side’s arguments, use their questions to make points, and ask questions that prove or disprove theories they know other Justices hold. When listening to both of Dave’s oral arguments for Knick, you can hear some nerves in his voice. But on that day, Dave was the Williamson County expert in the room, and he answered each volley of questions accordingly.

“You have to have confidence in your case so when you get peppered with these questions, you’re not going to let it affect you,” he explains. “My confidence comes from knowing that this is a good case, I’m on the right side, and my position is right. It’s like being in an argument where you don’t argue, you listen and answer. And then after it’s all over, you just hope that five of them agree with you.”

Getting Good News in Mexico

The Washington, DC, fervor is on full display on Supreme Court decision days. Outside the Court steps there are reporters, advocates, and usually some protestors for whatever issues are being debated that term.

Decisions are still delivered via printed-out paper packets in brown boxes carried into the Court. The more boxes, the more cases being delivered that day. The Court doesn’t announce what decisions will be handed out on which day, so each morning is a guessing game of what decision will appear.

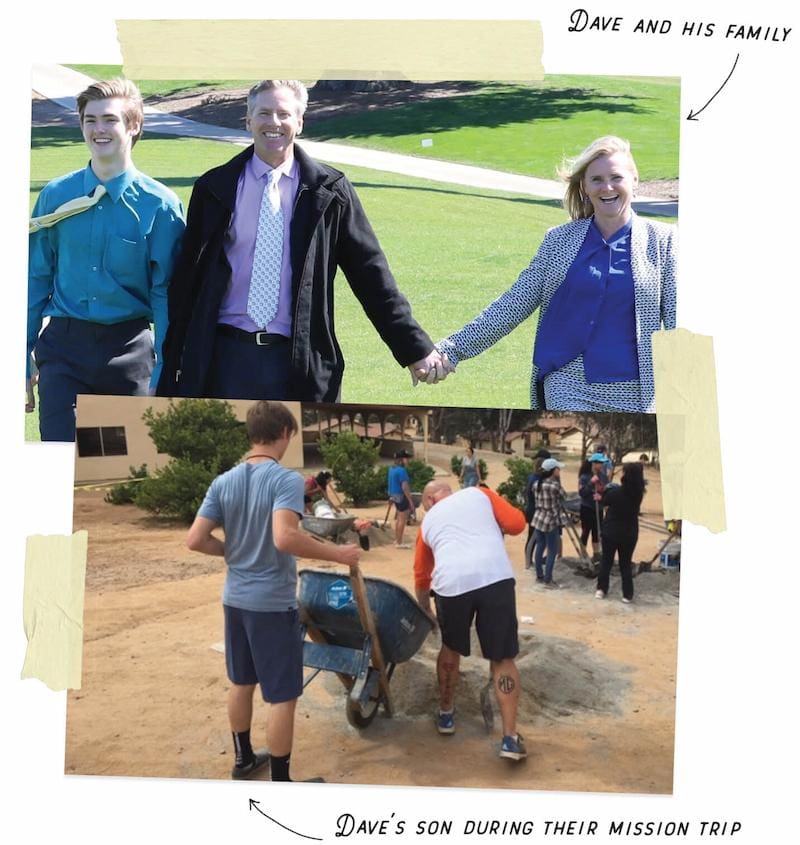

But on the day Knick was decided, June 21, 2019, Dave wasn’t in DC. And he wasn’t frantically hitting “refresh” on his computer’s web browser like many of his PLF col-leagues. Dave wasn’t even in the country. On June 21, 2019, what would be one of the biggest days of his professional life, Dave Breemer and his son were at an orphanage in Mexico volunteering on a mission trip with their church.

When explaining his emotions on that day, Dave, true to form, is a master of understatement. “It was interesting to be in Mexico when I got the news because, for one thing, there’s not great cell reception there so you feel a little bit detached. But it’s kind of cool. I don’t know, I probably would have reacted the same way anywhere. I was just happy it was done and it came out the right way.

“I was very thankful and grateful, I said some more prayers of thankfulness and went on with my life.”

In the Hollywood version of Dave’s story, Dave would start cleaning out his office of all his Williamson County research: yellowed papers and highlighted, dog-eared law review articles that he had collected over the years with all his cases. A satisfied smile on his face for a job well done.

But this isn’t Hollywood. And Dave isn’t interested in the earnest end scene. On our last phone call, I asked him if he had any other thoughts or feelings on his fight against Williamson County now that he was a few months removed from the victory.

I should have known what to expect.

“Not really. I’m glad it’s over,” he said. “Now I’m on to beat Penn Central v. New York City.”

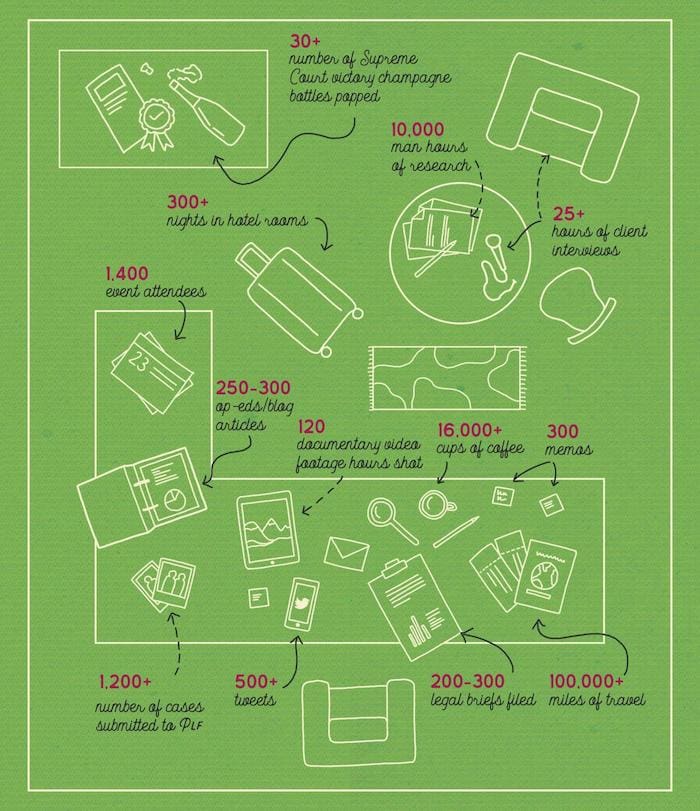

16,000 cups of coffee later, PLF measures a year in public interest law